[Transcript]

Hello, and welcome to America’s First Ladies. I’m your host, Risa Weaver-Enion.

Episode 2.1 Abigail’s Early Years

Welcome back for Season 2 of America’s First Ladies! I hope you enjoyed Season 1 about Martha Washington as much as I enjoyed preparing it. This season we’re diving into America’s second First Lady, Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams.

In many ways, Abigail Adams is the opposite of Martha Washington. She was a New Englander, rather than a southerner. She was only married once, and not all of her children pre-deceased her. Her husband was a lawyer, writer, and diplomat, rather than a general. And she spent several years living in Europe, whereas Martha never left the United States.

But Abigail and Martha were contemporaries, and even something like friends. They only met when their husbands were serving as the first president and vice president, but they spent a lot of time entertaining together during those years. And Abigail asked Martha for advice on how to be First Lady after John Adams won the election of 1796.

One huge difference between Abigail and Martha is that we have way more of Abigail’s letters as a primary source. Whereas Martha burned all her correspondence with George after his death and we only have some of her letters to other people, Abigail and John’s correspondence survives. And because they were apart for long stretches of time, there are a LOT of letters.

Abigail was a compulsive letter-writer. She wrote not only to John, but to her sisters, to her children, to other Congressmen and Founding Fathers, and to a huge number of friends and acquaintances. There are literally thousands of surviving letters from Abigail Adams’s life, and they provide a wealth of information.

I read six biographies to prepare for this season, and they all quote liberally from Abigail’s letters, so I will do the same. When I’m quoting Abigail directly, I won’t identify which book it came from, because a lot of them use the same quotes, and sometimes I take one part of a quote from one book, but another part of the same passage from a different book. But when I’m quoting an author, I will tell you which book it’s from. I’ll list all of them with links on the show website in case you’re interested in reading any of them.

Because Abigail and Martha lived through the same great events, there is some historical overlap between this season and last season. We’ll talk about some of the same things, but from a different perspective. During the war years, you’ll hear less about what was happening on the battlefield and more about what was happening in Congress, because that’s where John spent the first half of the war.

But before we get to all that, we must start at the beginning, on November 22, 1744, when Abigail Smith was born in Weymouth, Massachusetts. Abigail’s father was Reverend William Smith, who would eventually be the longest-serving minister of Weymouth Church. She was born in the parsonage where the Smith family lived.

Her mother was Elizabeth Quincy Smith, daughter of John and Elizabeth Quincy, who were one of the most prominent families in the colony of Massachusetts. The Quincy family had arrived in Massachusetts in 1633, only three years after it was founded.

Abigail Smith was the second of John and Elizabeth Smith’s three daughters. Mary had been born in 1741, and Elizabeth, nicknamed Betsy, was born in 1750. There was also a brother, William, who was born in 1746.

Weymouth was 14 miles southeast of Boston, which was by far the largest city (really, the only city) in Massachusetts. It was on the coast, and the area was made up of cultivated farms mixed with low, steep hills. Salt marshes covered the lowlands, and the heights were wooded.

Buildings in Weymouth were spaced widely, which protected them from the fires that often heavily damaged Boston. There was also a great earthquake in 1755 that leveled solid brick buildings in Boston, but only resulted in a bit of shaking in Weymouth.

Young Abigail was fair and dark-haired. She had wide-set eyes and was a bit frail, often ill as a child, and throughout her adult life. She liked helping her father with chores, and he gave her a pet lamb when she was 10.

Abigail had no formal school education because girls were rarely sent to school in those days. There were a couple of schools in Massachusetts that enrolled girls, but they were far away from home, and her parents wanted to keep her close due to her frequent illnesses. It’s possible that cost was also a concern. The Smith family wasn’t poor, but they also weren’t wealthy. Their income came from a combination of Reverend Smith’s small salary as minister, the production of his farm, and some land that Elizabeth had received from her parents.

Abigail’s mother Elizabeth taught her to read and write, and she learned enough math to run a household, which was all that was expected of colonial girls. She was also taught to cook, sew, clean, raise vegetables and chickens, and nurse the sick. The children all had household chores, even though the family had servants.

At least a few of the Smith family servants were enslaved, but Abigail herself never owned slaves, and was outspoken against slavery. The Smith family produced most of their own food by gardening, hunting, fishing, or butchering animals. Abigail and her siblings would plant, weed, and tend the gardens, prepare fruits and vegetables for winter storage, help smoke and salt fish and meat, bake bread, make soap and candles, and mix herbal medicines.

Abigail felt stifled as a child, and thought her mother was overly cautious and protective of her, writing, “My Mother makes bugbears sometimes, and then seems uneasy because I will not be scared by them.”

Her mother had good reason to worry, given the high rates of infant and childhood mortality in the 18th century. There was an epidemic of diphtheria (called throat distemper back then) in 1751, which killed dozens of Weymouth children, but none of the Smith children. They also survived a measles epidemic in 1759, and managed to escape from many smallpox epidemics that ravaged Boston during their childhoods.

Religion was a huge part of Abigail’s life, and not just because her father was a minister. New England had been founded by the Puritans, so religion was a huge part of everyone’s life. It’s worth taking a slight detour to explain a bit more about the Puritans and the founders of the colony of Massachusetts. This is going to be a very high-level review, so if you’re an expert on religion, don’t come at me.

In 1534, King Henry VIII of England wanted to divorce his wife, but the Pope wouldn’t let him. So he broke England away from the Catholic Church and created the Church of England, with himself as the head of the church instead of the Pope. The Church of England is also known as the Anglican Church.

This took place during the larger Protestant Reformation that was occurring throughout Europe and had started in the early 1500s. I’m sure you’ve heard of Martin Luther and John Calvin, mainly because Lutheranism and Calvinism are named after them.

The Church of England was considered a Calvinist church during the reign of Henry’s daughter Elizabeth I (she reigned from 1558-1603). However, it maintained quite a few similarities to the Catholic Church, and in the 1600s, reformers wanted to do away with those vestiges of Catholicism, especially clerical vestments, wedding rings, organ music in church, kneeling during communion, using the word “priest” for ministers, and making the sign of the cross at baptism and communion. These reformers were called Puritans, because they wanted to “purify” the church of Catholic practices.

The Puritans didn’t call themselves Puritans, because it was mostly used as a negative term by people who didn’t agree with them. During the reign of Charles I of England (from 1625-1649) many Puritans emigrated from Britain to the “New World” to escape religious conflicts at home. Massachusetts was founded by some of these emigrées.

Abigail’s religion was categorized as Congregationalist. In short, Congregationalists believed that only genuine believers should be part of the church. The church members made up the congregation. They believed that ministers should be ordained by the congregation rather than by bishops, and that the congregation should govern the church.

In her book, Abigail and John: Portrait of a Marriage, Edith Gelles explains how this Congregationalist upbringing affected Abigail’s life:

“Service was a primary virtue, even when it meant sacrifice. Hard work was a value because too great leisure was indulgent. Giving to others meant creating communities, and no individual could live outside a community, be it the family, the village, or the nation. These ideals, planted early in life, as the Smiths did with Abigail and the Adamses did with John, were in turn translated by them into a word they commonly used with their own children: duty. Duty, in the Puritan sense of virtue and sacrifice, service and love, was the foundation of a good life.”

Aside from having an overprotective mother, Abigail enjoyed a reasonably carefree childhood. She once referred to her youth as her “early, wild, and giddy days,” leading her Grandmother Quincy to remark that “wild colts make the best Horses.”

Abigail spent a good deal of time at the mansion of her Quincy grandparents, called Mount Wollaston. She frequently walked the 8-mile round trip from her house to Mount Wollaston, where her grandfather made his extensive library available to her. Throughout her life, Abigail was an avid reader. She always regretted not being able to attend school, and female education was a cause dear to her heart.

In a letter years later to her daughter, Abigail recalled the influence of her Grandmother Quincy, writing, “I have not forgotten the excellent lessons which I received from my grandmother, at a very early period of life….Whether it was owing to the happy method of mixing instruction and amusement together…I know not….I love and revere her memory; her lively, cheerful disposition animated all around her.”

In her teenage years, Abigail often visited her aunt and uncle in Boston, Isaac and Elizabeth Smith. She was close friends with her cousin, Isaac Smith, Jr., as well as Aunt Elizabeth’s younger sister, Hannah Storer. Hannah was six years older than Abigail, while Isaac Jr. was five years younger. When they weren’t together, they wrote frequent letters to each other.

These letters weren’t merely social and conversational; they were also an opportunity to teach and learn from each other. Abigail and her friends often discussed books and ideas, mixed in with the usual teenage gossip.

Sometime around 1756, when Abigail was around 11 years old and her sister Mary was around 14 or 15, a man named Richard Cranch began courting Mary. Let’s leave aside for the moment the fact that Richard Cranch was 30 at the time. He was useful to Abigail because he helped her learn French, brought her books to read, and introduced her to English literature.

Abigail later wrote that Richard was the first person who “put proper Bookes into my hands, who taught me to love the Poets and to distinguish their Merrits.” She attributed to him “my early taste for letters; and for the nurture and cultivation of those qualities which have since afforded me much pleasure and satisfaction.”

Richard was useful in another sense, because he was friends with a young lawyer named John Adams, and that’s how Abigail met her future husband.

John Adams was born October 30, 1735, in Braintree, Massachusetts, which was another small town outside of Boston, about 10 miles from the city. His father, also named John, was a farmer, and his mother, Susanna Boylston Adams, was from a prominent family, but not as prominent as the Quincys. Much like Abigail’s parents, there was a status mis-match between John’s parents.

John flirted with the idea of becoming a farmer like his father, but the elder John wanted a different life for his son. He insisted that John attend Harvard and become a minister. At that time, Harvard consisted of four red-brick buildings, a small chapel, seven faculty members, and about 100 students. John’s graduating class of 1755 was only 27 students in total.

John wasn’t keen on the idea of becoming a minister, and at some point during his Harvard years he joined a debating and discussion club. He was told he had skill at public speaking and would make a better lawyer than a preacher.

In those days, there were no law schools, and one could only become a lawyer after apprenticing with a practicing attorney and then applying to join the bar. There was an apprentice fee involved, so after graduating, John found work as a school teacher in another small town, Worcester, to earn enough money to pay the apprentice fee.

After apprenticing with James Putnam, a young Worcester attorney, John returned to Braintree in 1758, and then was admitted to the bar in a ceremony at the Superior Court of Boston on November 6, 1759, just after his 24th birthday. And this is where John and Abigail’s stories converge.

They met in the summer of 1759, when Abigail was 14 and John was 23. He was not impressed at first. Sometimes quoting directly from primary sources is tricky because of the way the meaning of words has changed over the course of hundreds of years. John’s initial thoughts on Abigail and Mary are better summarized by Woody Holton in his book Abigail Adams: A Life:

“Calling Mary and Abigail by their childhood nicknames, Adams declared that ‘Polly and Nabby are Wits.’ For Adams, that was no compliment, especially when the subjects were women—and young ones at that. Later in the same diary entry, Adams asked himself whether the Smith girls were ‘either Frank or fond, or even candid.’ In the eighteenth century, the word candid did not mean, as it does today, ‘blunt.’ As Adams noted in the same diary entry, ‘Candor is a Disposition to palliate faults and Mistakes, to put the best Construction upon Words and Actions, and to forgive Injuries.’ Perhaps the closest modern synonym would be nonjudgmental. Apparently the Smith girls had shown Adams their lack of candor by wittily passing judgment on something he had done or said. They had made fun of him. For a man whose defining sin was vanity, there could scarcely have been an unkinder cut.”

But John’s unfavorable opinion of Abigail didn’t last, and by the end of 1761, he was smitten. He had spent a great deal more time with Abigail and Mary since their initial meeting, as his good friend Richard courted Mary. John described 17-year-old Abigail in his diary as “a constant feast….Prudent, modest, delicate, soft, sensible, obliging, active.” A word he used to describe her throughout their life together was “saucy.” Apparently her wit was now a positive quality, rather than a negative one.

We don’t have Abigail’s early thoughts on John because she didn’t keep a diary, and there aren’t many surviving letters from this period of her life. We do know that she did not have a lot of suitors; in fact, John may have been the only one. In response to a letter from her friend Hannah Lincoln, Abigail wrote that Hannah implied that suitors were “as plenty as herrings” around the parsonage. But in reality, there was “as great a scarcity of them as there is of justice, honesty, prudence, and many other virtues. Wealth, wealth is the only thing that is looked after now.”

Abigail’s sister Mary married Richard Cranch in November 1762, and John continued his courtship of Abigail. Unsurprisingly, they traded many letters. What’s probably more surprising to a modern audience is that they didn’t address each other by name.

It was common practice back then for people to assume the names of classical characters from myth, history, or literature. Abigail wrote as Diana, Roman goddess of the hunt, and John wrote as Lysander, a hero of ancient Sparta. He also sometimes addressed Abigail as Miss Adorable, which is cringe-inducing to look back on.

In fact, most of the letters they traded during these years of courtship are pretty silly and florid. It actually makes me a little glad that we don’t have the letters from when George Washington was courting Patsy Custis. No one wants to think of the Founding Fathers as being silly boys in love.

I’ll give you a small taste, so you can judge for yourself. In August 1763, John wrote to Abigail that he had “dreamed, I saw a Lady, tripping it over the Hills, on Weymouth shore, and Spreading Light and Beauty and Glory, all around her. At first I thought it was Aurora, with her fair Complexion, her Crimson Blushes, and her million Charms and Graces. But I soon found it was Diana, a Lady infinitely dearer to me and more charming.”

They also teased each other quite a bit in these letters. A lot of the things they wrote are nonsensical to a modern audience, but one funny retort came from Abigail after John made fun of her for her parrot-toed way of walking. She replied, “a gentleman has no business to concern himself about the legs of a lady.”

At any rate, by early 1764, Abigail and John wanted to marry. There had been some hesitation about the match on her mother’s part. Adams family lore says that it was because his family was of middling quality and the law was a disreputable profession, but there’s no hard evidence that this was the reason why Elizabeth Smith was hesitant. But by spring 1764 Abigail’s parents had consented, and they were making wedding plans when a smallpox epidemic put everything on hold.

We talked quite a bit about smallpox in season 1. Boston actually had a law against smallpox inoculation, but in the middle of an epidemic, the law was mostly ignored, and large numbers of people chose to be inoculated, including John. Abigail wanted to be inoculated, but her mother wouldn’t allow it.

So just when Abigail and John were hoping to be married, they were instead separated for six weeks while John stayed in Boston to prepare for and then recover from inoculation. Inoculation with a live virus always carries the risk of severe illness and potentially death, but John seems to have had a reasonably easy experience. Interestingly, it was John’s great uncle Zabdiel Boylston who had introduced inoculation to Boston in 1721.

He and Abigail wrote to each other constantly during this time apart. John’s letters to her were smoked before being turned over to the messenger, and then smoked again before being given to Abigail. The hope was that the smoke would kill any smallpox on the papers, but that’s not how smallpox works. The risk of contracting smallpox via paper contamination was small though, so despite the uselessness of smoking the letters, Abigail never caught smallpox.

John sent Abigail a vivid description of his inoculation. “Dr. Perkins demanded my left Arm and Dr. Warren my Brothers. They took their Launcetts and with their Points divided the skin for about a quarter of an Inch and just suffering the Blood to appear, buried a Thread about a Quarter inch long in the Channell. A little Lint was then laid over the scratch and a Piece of Ragg pressed on, and then a Bandage bound over all.”

He also described his symptoms. “I had no Pain in my Back, none in my side, none in my Head None in my Bones or Limbs, no retching or vomiting or sickness. A short shivering Fit, and a succeeding hot glowing Fit, a Want of Appetite, and a general Languor, were all the symptoms…that I can Boast of.”

By May 1764 John had recovered from inoculation and was back on the court circuit. This is another reason why he and Abigail had to communicate by letter so much of the time. Courts were convened seasonally throughout the small towns and villages of Massachusetts, and John had to travel to different courts to argue different cases on behalf of his clients.

Before they could be married though, they had one more separation of several weeks to endure. Abigail took a trip to Boston to visit her aunt and uncle and fell ill while there, and John was in Plymouth arguing a case. He wrote to her,

“Oh my dear girl, I thank heaven that another fortnight will restore you to me—after so long a separation. My soul and body have both been thrown into disorder by your absence, and a month or two more would make me the most insufferable cynic in the world. I see nothing but faults, follies, frailties and defects in anybody lately. People have lost all their good properties or I my justice or discernment.

But you who have always softened and warmed my heart, shall restore my benevolence as well as my health and tranquility of mind. You shall polish and refine my sentiments of life and manners, banish all the unsocial and ill natured particles in my composition, and form me to that happy temper that can reconcile a quick discernment with a perfect candor.

Believe me, now and ever your faithful Lysander”

This wouldn’t be the last time that John would heavily rely on Abigail to soften his harder edges and be a source of support for him.

On October 25, 1764, Abigail and John were finally married in the family parsonage, with Abigail's father Reverend Smith officiating. Weddings in Puritan New England were rather simple. A minister read out loud the contract joining the bride and groom. They didn’t even repeat the words back; they just confirmed their agreement to be joined. Weddings typically took place in the bride’s home with family and friends in attendance, and then the men and women went to separate rooms to celebrate. This really couldn’t be more different from the Virginia tradition of dancing, feasting, and drinking for a week.

Abigail and John left Weymouth on the very night of their wedding and went to Braintree. When John’s father had died in 1761, he left John a house that was next-door to the house where John grew up. John’s brother Peter and his widowed mother Susanna lived in the family house, and Abigail was likely somewhat apprehensive about living so close to her mother-in-law. She needn’t have worried though. She and Susanna Adams got along quite well, and were close for many years.

When they married, Abigail was a month short of her 20th birthday, and John was just about to turn 29. Abigail was a bit on the young side to be getting married. A more typical age for a New England bride was 23. But her sister Mary had also married at the young age of 21. John had purposely delayed marrying until he was more secure in his profession as a lawyer. It was a husband’s duty to provide for his wife and family, and there was no sense in having a family until you could provide for them. Abigail and John would often give this advice to their children in later years.

Let’s turn to the biographies for a description of the couple at the time they married. According to Barbara Somervill, in her book Abigail Adams: Courageous Patriot and First Lady, Abigail “was not pretty by society’s standards. Most people probably would have called her ‘interesting.’ Her face was oval with a sharp, pointy chin, and she had a long, thin nose and narrow lips. Her most striking feature must have been her eyes, which were described as brilliant, piercing dark brown. John, on the other hand, had a round, fleshy face, a lumpy nose, a stout body, and stubby legs. His blue eyes sank beneath thick, heavy eyelids.”

Perhaps Barbara is being overly critical. David McCullough offers a more favorable description of Abigail in his book, John Adams.

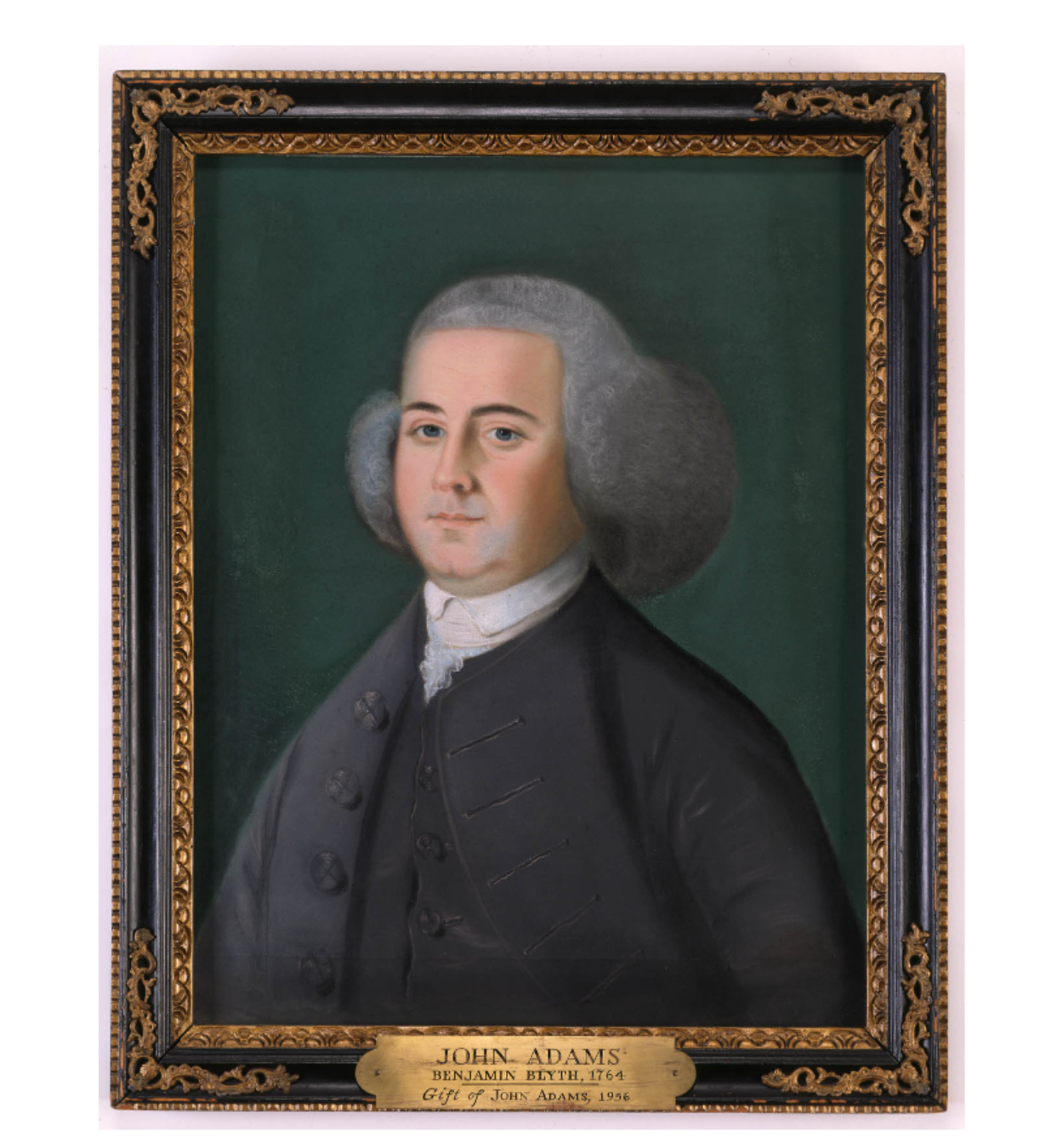

“By the time of her wedding, [Abigail was] little more than five feet tall, with dark brown hair, brown eyes, and a fine, pale complexion. For a rather stiff pastel portrait, one of a pair that she and John sat for in Salem a few years after their marriage, she posed with just a hint of a smile, three strands of pearls at the neck, her hair pulled back with a blue ribbon. But where the flat, oval face in her husband’s portrait conveyed nothing of his bristling intelligence and appetite for life, in hers there was a strong, unmistakable look of good sense and character. He could have been almost any well-fed, untested young man with dark, arched brows and a grey wig, while she was distinctively attractive, readily identifiable, her intent dark eyes clearly focused on the world.”

I’ll put photos of these portraits on the website so you can see for yourself. Just go to americasfirstladiespodcast.com/2.1 or click on the link in the show notes in your podcast player. We actually have quite a few portraits of Abigail and John over the years, so I’ll try to share them as we cover the different time periods when they were painted. When Gilbert Stuart painted Abigail in her mid-50s, he told a friend that he wished he could have painted her when she was young and that she must have been a “perfect Venus.”

Next week, we’ll join the Adamses at home in Braintree for the first 10 years of their marriage, the same time period that sees growing unrest between Great Britain and the American colonies.

Thanks for listening to this episode. It was produced by me, and the music is by Matthew Dull. If you’re enjoying learning about America’s First Ladies, please share this podcast with a friend!