[Transcript]

Hello, and welcome to America’s First Ladies. I’m your host, Risa Weaver-Enion.

Episode 2.13 Retirement to Peacefield

We left off last week at the very end of 1799. George Washington had died, and John’s three-man peace commission had sailed to France.

The year 1800 kicked off with gusto when word arrived in February that the French Republic had fallen. On November 9, General Napoleon Bonaparte had executed a coup and taken over the French government, declaring himself First Consul. He also declared that the French Revolution was over. John had always suspected that the French Revolution would end in dictatorship; he was sad to be right.

Abigail enjoyed good health through the winter of 1799-1800. Nabby and her daughter Caroline were with her in Philadelphia. Nabby’s two boys had been sent to Abigail’s sister Elizabeth Peabody and her husband to board with them and be tutored by Stephen Peabody. Nabby’s husband William was not quite as disgraced as Charles, but it was quite clear he was never going to amount to anything. Thomas was also in Philadelphia, having returned from his position with John Quincy in Europe the previous winter. He was working as a lawyer in Philadelphia.

It was by no means certain that John would win reelection, as Washington had. What was certain was that Vice President Jefferson would be the Republican candidate for president in the 1800 election. In February, John apparently had decided to at least stand for reelection, pitting, for the first and only time in history, the president and vice president against each other in the presidential election. Abigail wrote, “if his country calls him to continue longer in Her service, I doubt not that he will be obedient to her voice, in which case I certainly should consider it my duty to accompany him.”

John made several important moves in the spring of 1800. On April 24, he signed legislation approving funds to purchase the necessary books to create a Library of Congress. And in May, finally fed up with his own Cabinet members conspiring with Hamilton behind his back, he fired Secretary of War McHenry and Secretary of State Pickering. In their places he appointed Samuel Dexter, a senator from Massachusetts, as Secretary of War and John Marshall, who was a House member, as Secretary of State.

Now that war with France was exceedingly unlikely, there was no need for the army. Congress voted to disband the army by summer, leaving Hamilton out in the cold once more. He immediately began conspiring to unseat John in the presidential election.

Abigail left Philadelphia for the last time on May 19, 1800. The nation’s capital was scheduled to move to the new city on the Potomac in June. She stopped in New York City on her way home to see Charles. She wrote to John Quincy that she had hoped to see some change in Charles, but all she saw was that “vice and destruction have swallowed him up. All is lost—poor, poor, unhappy, wretched man.” Sally had taken Abbe to live with her at her mother’s and now Abigail took Susanna back to Quincy with her.

John left Philadelphia on May 27 and went to inspect the new capital, which was being called Federal City, but was officially named the District of Columbia. It would also come to be called Washington City.

Calling Federal City a “city” was a misnomer. David McCullough describes it as “a rather shabby village and great stretches of tree stumps, stubble, and swamp. There were no schools, not a single church. Capitol Hill comprised a few stores, a few nondescript hotels and boardinghouses clustered near a half-finished sandstone Capitol. … only one structure had been completed, the Treasury, a plain two-story brick building a mile to the west of the Capitol, next door to the new President’s House, which was still a long way from being ready.”

After a visit to Federal City, Oliver Wolcott had written to his wife, “I cannot but consider our Presidents as very unfortunate men if they must live in this dwelling. It must be cold and damp in winter. …It was built to be looked at by visitors and strangers, and will render its occupants an object of ridicule with some and pity with others.” Not a great review. Zero stars. Do not recommend.

John seems to have been pleased though, writing to Abigail, “I like the seat of government very well.” He stayed for about 10 days, and then left for Quincy on June 14, leaving new Secretary of State Marshall in charge.

John was well-received by citizens on his journey north, but the summer of 1800 was full of vitriolic attacks on both sides. The Sedition Act was only ever used to prosecute Republicans, because it prohibited attacks on “the government” and “the government” was Federalist. The papers printed the most ridiculous things.

The Republican press claimed that only the intervention of George Washington had prevented John from marrying his son to a daughter of King George III, creating a new dynasty to rule over both England and America. There are so many things wrong with that, I can’t even. They also accused John of sending Charles Cotesworth Pinckney to London to procure four pretty mistresses that they could divide between them. John reacted to this with humor, writing to a friend, “I do declare upon my honor, if this is true General Pinckney has kept them all for himself and cheated me out of my two.”

For their part, the Federalist press absurdly claimed that Jefferson planned to make the United States an atheist country and then turn it over to Napoleon. He was accused of favoring states’ rights (which, to be fair, he did), of being a spendthrift (which he was, and we’ll hear more about that next season), and of being unfaithful to the Constitution, which was the most untrue thing of the bunch.

John left Quincy in October to head to Federal City. Abigail followed close behind him, stopping in New York to see Charles again. John had renounced Charles, and refused to stop and see him. Abigail found Charles sick in bed at the home of a kind friend who had taken him in. After she left, she wrote that “a distressing cough, an affliction of the liver, and a dropsy will soon terminate a Life, which might have been made valuable to himself and others.” Three weeks later, Charles died at the age of 30. Abigail would later write to Mary, “I know, my much loved Sister, that you will mingle in my sorrow and weep with me over the Grave of a poor unhappy child…He was beloved, in spite of his Errors, and all spoke with grief and sorrow for his habits.”

Abigail arrived into Federal City on November 16, a day behind schedule after getting lost in the woods between Baltimore and the capital. She found the President’s House still unfinished. Damp plaster walls made all the rooms too chilly to inhabit unless the fire was burning. The main stairway to the second floor had not yet been built. Abigail estimated that it would require at least 30 servants to staff the house, but she tried to get by with only 6. A job made much more difficult by the fact that bells to summon them had not yet been installed.

They made the best of it. After his first night in the new house, John had written in a letter to Abigail, “I pray Heaven to bestow the best of Blessings on this House and on all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise Men ever rule under this roof!”

In case it’s not clear, sometimes I include these quotes because their irony with the benefit of hindsight is just too much.

In November John received news he had been waiting for: a treaty had been signed with France on October 3. The undeclared war with the French, the Quasi-War as it was usually referred to, was finally over.

The news arrived too late to have any impact on the election of 1800. The electors met on December 4 to cast their ballots. Once it was known that South Carolina, a Federalist stronghold, had given its votes to the Republicans, John and Abigail knew the election was lost. When the results were officially counted and certified, Jefferson and Aaron Burr had tied with 73 votes each. John received 65 votes, and Pinckney, the candidate Hamilton had tried to push ahead of John, got 63.

Abigail wrote of the choice between Jefferson and Burr, “What a lesson upon Elective Governments have we in our young Republic of 12 years old? I have turned and overturned in my mind at various time the merits and demerits of the two candidates. Long acquaintance, private friendship and the full belief that the private Character of one is much purer than the other, inclines me to him who has certainly from Age, succession and public employment the prior Right. Yet when I reflect upon the visionary system of Government which will undoubtedly be adopted, the Evils which must result from it to the Country, I am sometimes inclined to believe that the more bold, daring and decisive Character would succeed in supporting a Government for a longer time.”

On January 1, 1801, Abigail and John hosted the first New Year’s Day reception at the new President’s House. A few days later, they invited Jefferson to dine with them and some members of Congress. Then on February 7, Abigail hosted her final dinner party as First Lady.

The electoral votes were counted on February 11, and the House immediately began voting to break the electoral college tie. But they were deadlocked, and there was still no result when Abigail left the capital on February 13 to go home to Quincy. Finally, on February 17, 1801, on the 36th ballot, James Bayard of Delaware switched his vote, and Jefferson was declared the winner of the presidency with Burr as runner-up and vice president.

John spent his last weeks in office naming judges to the courts, including John Marshall as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court to replace Oliver Ellsworth, who had resigned. Jefferson would later decry these as “midnight appointments,” but that’s a misleading characterization. They were all thoughtful appointments, and made weeks before the end of John’s term, not on the very last night of it. He had mostly been waiting for Congress to pass an act expanding the judiciary, which had been proposed over a year previously. Most of John’s appointments were to the new seats on various courts. One of his very last acts as president was to recall his son John Quincy from his diplomatic post in Europe.

Jefferson was inaugurated on March 4, 1801. John did not attend. Instead, he slipped away from Federal City in the early hours of the morning, accompanied only by his secretary and nephew William Shaw and his faithful servant John Briesler. Finally, after 27 years of public service, Abigail and John Adams could retire to a private life.

John arrived home on March 18, and from that point forward, he and Abigail would never have occasion to write another letter to one another, because they were never again separated. In fact, they had 10 days of forced togetherness when a fierce winter storm snowed them in immediately upon John’s return.

Abigail’s niece, Louisa Smith, still lived with them, and they were joined by Charles’s widow Sally and her two daughters. Nabby and her children came to spend the summer. In the fall, they were delighted by a visit from John Quincy, his wife Louisa, and their baby son, George Washington Adams. The baby had been born in April while they were still in Berlin, and they had sailed into New York in September. This was Abigail and John’s first chance to meet Louisa, and they both approved.

John Quincy purchased a home in Boston, and he intended to take up his law practice again. He would eventually be elected to the Massachusetts state senate, then to the U.S. Senate, and finally to the presidency after more diplomatic missions abroad. He and Louisa provided Abigail and John with three more grandchildren: a boy named John Adams after his grandfather, a girl named Louisa after her mother, and another boy named Charles Francis in honor of his deceased uncle. We’ll hear much more about John Quincy and Louisa Catherine Adams in season 6.

Thomas was still in the law in Philadelphia. He eventually moved back to Quincy, became a judge, married a woman named Ann Harrod in 1805, and gave Abigail and John seven grandchildren: three granddaughters and four grandsons, all but one of whom lived into adulthood. They named their firstborn Abigail Smith Adams.

Abigail and John resumed their country life without any hesitations. John was happy to be back in the fields, and his diary was full of reports of how many loads of hay had been transported and how the various farm projects were proceeding. Abigail wrote to Thomas, “You will find your father in his fields, attending to his hay-makers. The crops of hay have been abundant.”

Abigail was happy to have her house full of her children and grandchildren during various visits and occasions. As Edith Gelles puts it in her book, Abigail and John: Portrait of a Marriage, “Over all of this commotion, Abigail presided as hostess, sometimes as cook and housekeeper, partly because of her energy, which was too prodigious to retire in the face of work that needed to be done. Mostly, however, it conformed to her ethic of hospitality. ‘To be attentive to our guests is not only true kindness, but true politeness; for if there is a virtue which is its own reward, hospitality is that virtue,’ she explained to her granddaughter.”

Both John and Abigail continued to suffer from various colds and injuries, including frequent flareups of Abigail’s old rheumatism. They never again left Massachusetts, traveling only as far as Boston or a neighboring village.

In 1804, Abigail resumed her correspondence with Thomas Jefferson when she learned of the death of his daughter Polly, the young girl who had stayed with her in London for a few days all those years ago. Abigail and John had not written to Jefferson since leaving the capital city in 1801. John and Jefferson would not resume their correspondence for several more years, but Abigail and Jefferson wrote to each other regularly for some time.

One person Abigail and John would never forgive was Hamilton. When he was killed in a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804, John Quincy spoke for the family by refusing to attend a memorial service, writing that he would not “join in any outward demonstrations of regret [that I] could not feel at heart.” Abigail wrote, “Why deceive the public and give that which is more than due and leave nothing to bestow upon fairer and purer Characters?...he was the Idol of a party…who have injured their cause, and their Country more than Hamilton ever served it.”

The year 1811 was a very difficult one for the Adams family. Thomas was thrown from his horse and badly injured, Abigail’s sister Mary Cranch was dying of tuberculosis, and Charles’s widow Sally was spitting up blood. John ripped open his leg after tripping over a stake in the ground and was confined to the house for months. Then Nabby found a lump in her breast.

After consulting several doctors, Nabby decided to have the entire breast removed. The surgery, which, mind you, was performed without anesthesia, took place in Quincy on October 8. Two days later, Richard Cranch died of heart failure, followed by his wife Mary the very next day. For Abigail, the loss of her dear sister was the hardest thing she had had to bear since Charles’s death 11 years earlier.

The sadness of 1811 was rivaled by 1813. John Quincy and Louisa were living in Russia where he was serving as ambassador. In early 1813, Abigail and John received the news that their granddaughter Louisa had died a few months prior, shortly after her first birthday. Thomas and his wife Ann had also lost a young daughter at the end of 1812. The loss of these two toddlers, both girls, brought back painful memories of Abigail and John’s loss of their daughter Susanna, who had died at the age of 13 months. Abigail wrote to Louisa to commiserate with her on their similar losses, “Early in life I was called to taste the bitter cup. [The intervening years have] not obliterated from my mind the anguish of my soul upon the occasion.”

Also in 1813, Nabby’s breast cancer came back. It was much worse, and had spread throughout her body. Abigail was too old and frail to journey to Nabby, who was still living in the backwoods of New York, but Nabby decided she couldn’t die anywhere but her parents’ house. She and two of her adult children made the 300-mile journey to Quincy, which took them nearly two months. They arrived on July 26, and Nabby died on August 15 at the age of 49. Her ne-er do well husband William had been in Washington where he was serving in the House of Representatives, but he made it to Quincy the day before she died.

The loss of her only living daughter, on top of the loss of the Cranches and two baby grandchildren aged Abigail in a severe way. A long-time friend visited them late in 1813 and was thunderstruck when he realized that the elderly lady before him was Abigail.

Abigail became a great-grandmother on March 19, 1814 when Nabby’s eldest son, William Steuben Smith and his wife Catherine Johnson Smith had a baby girl. And here’s a little mind-bending fun fact for you: William’s wife Catherine was Louisa Catherine Adams’s younger sister. So John Quincy’s wife was both sister-in-law and aunt by marriage to William Steuben Smith.

Death kept coming for Abigail’s family. In 1815 her cousin Cotton Tufts died, followed by her last remaining sister, Elizabeth, in 1816. Also in 1816 they received word that Nabby’s husband William had died. Amidst all this bad news, Abigail prepared her will. She made arrangements for Louisa Smith, who was still unmarried and had long been Abigail’s closest companion, to receive $1200, which would be worth about $28,000 today. Through very complicated arrangements I won’t get into, Abigail owned half of a farm she had inherited from her father; this she left to Thomas. To John Quincy she left a different farm she had received from an uncle on her mother’s side.

The main bequests of her will were personal belongings and small stipends so that none of her female relatives or servants would have to worry about having the money to purchase the traditional mourning ring and dress when Abigail died. She distributed her jewelry, gowns, household goods, and $4000 cash among her granddaughters, nieces, her brother William’s widow, two distant cousins, and two servants. To her grandsons, nephews, and male servants she left nothing, figuring that they were boys and had enough advantages already.

The most remarkable thing about this will is that it existed at all. As a married woman whose husband was still alive, Abigail had no legal right to own or bequeath anything. But she did, and John carried out the terms of her will to the letter. Further proof that theirs was a marriage of equals, even though they lived in a time when that was exceptionally rare.

The day after Abigail and John’s 50th wedding anniversary, October 25, 1814, Abigail wrote to her granddaughter Caroline, “Yesterday completed half a century since I entered the married state, then just your age. I have great cause of thankfulness that I have lived so long, and enojoyed so large a portion of happiness as has been my lot. The greatest source of unhappiness I have known in that period, has arisen from the long and cruel separations which I was called in a time of war, and with a young family around me, to submit to.”

In a letter written to her sister Elizabeth around the same time she wrote, “After half a century, I can say, my choice would be the same if I again had youth.”

In August 1817, Abigail was very grateful to be able to welcome John Quincy and his family home from Europe. She didn’t think she would ever see any of them again, and was heartily glad to be wrong about that. Much like John’s mother thought she wouldn’t live to see John and Abigail return from Europe so many years before.

In late September 1818, Abigail came down with typhus. She was told to remain in bed, and to not move or speak. John was despondent. In letters to various friends he wrote, “The dear partner of my life for fifty-four years as a wife … now lies in extremis, forbidden to speak or be spoken to. She has recovered from a similar state once before, and she may again, but typhoid…at 74 years of age is enough to create alarm.”

Abigail was ready to face death, and despite the prohibition on talking, John recorded that she told him “she was going and if it was the will of heaven she was willing.” John was worried about the amount of pain she was in, telling one of the relatives keeping vigil at Abigail’s bedside, “I wish I could lay down beside her and die too…I cannot bear to see her in this state.”

Around 1 pm on October 28, 1818, Abigail Smith Adams died, three days after her 54th wedding anniversary and three weeks short of her 74th birthday. She was buried on November 1 in the graveyard across the street from the First Congregational Church.

John Quincy wrote in his diary, “My mother … was a minister of blessing to all human beings within her sphere of action. … She had no feelings but of kindness and beneficence. Yet her mind was as firm as her temper was mild and gentle. She…has been to me more than a mother. She has been a spirit from above watching over me for good…Never have I known another human being, the perpetual object of whose life, was so unremittingly to do good.”

At her funeral service, the reverend said, “Madame Adams possessed a mind elevated in its views and capable of attainments above the common order of intellects. … But though her attainments were great, and she had lived in the highest walks of society and was fitted for the lofty departments in which she acted, her elevation had never filled her soul with pride, or led her for a moment to forget the feelings and claims of others.”

Despite being nine years older than Abigail, John outlived her by nearly eight years. He continued to live in their house named Peacefield, tending to his farm, reading, and spending time with his family. He lived long enough to see his eldest son John Quincy elected as the sixth president of the United States.

And then, in a twist that not even a fiction writer would dare to craft, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died on the same day within hours of each other. The date was July 4, 1826—the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

John was buried next to his wife in the graveyard at First Congregationalist Church.

And that brings us to the end of season 2. I have no doubt that at some point in this series we’ll get to a woman who wasn’t remarkable. Not every First Lady can be as incredible as Martha Washington and Abigail Adams. And certainly not every President has been as capable and dedicated as George Washington and John Adams were. If we’ve learned one overarching thing from the first two seasons of this podcast it’s that these great Founding Fathers never could have been as great as they were without their wives.

Edith Gelles summed up Abigail as First Lady in her book, Abigail Adams: A Writing Life. When Abigail went to Philadelphia in May 1797 to take up her post as First Lady, “she did so reluctantly, with a sense of foreboding, conscious that the next years would be taxing on her health and her spirit. She forced herself to take the journey because it was her wifely duty to be beside John Adams but also because of her religiously founded sense of patriotic loyalty.

She entered with him into an enterprise that would have a lasting legacy for the nation but no lasting impact upon the role that she occupied. In the unique circumstances of the Adams administration, a structural vacuum existed that was filled by the First Lady, but not just any woman would have embraced her role in the manner of Abigail Adams. In the high station that she occupied, Abigail exercised authority with a personal combination of shrewdness, boldness, and humility. For many reasons—personal, social, and historical—Abigail’s tenure as First Lady was unique.”

Abigail was a remarkable woman, but she also had many advantages in life. There’s always a bit of luck or coincidence involved when someone rises to a prominent role in the world. Abigail was intelligent, well-spoken, and well-read. If the American Revolution had never happened, she would have lived her life as a well-regarded matron of Boston society. Her marriage and her family were always the most important things to her, and that would have been true even if she didn’t also happen to become famous along with her husband.

But Abigail also had her flaws. Like pretty much every other white person in the 18th century, she could be pretty racist, despite being anti-slavery. And some of what she wrote concerning foreigners and the press could literally be tweets from 2025. She was by no means perfect or always a good role model.

I want to end with a long quote from Charles Akers’s Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary American Woman, and not just because of the brilliant play on words in the title of his biography of her.

“The life of Abigail Adams was unlike that of contemporary American women. Most were poor and burdened with monotonous domestic labor; she always enjoyed relative affluence and never lived a day unattended by servants. Most had little or no educational opportunity; she was surrounded by books from the cradle to the grave. Most had no choice but to marry men who accepted female inferiority; she married a man who respected her intellect and valued her counsel. Most spent their lives in one location or in a succession of provincial communities; she lived in the leading metropolises of the western world. Most had little opportunity to acquire political knowledge; she conversed with statesmen in Europe and the United States and wrote long letters of political commentary. Few if any of her countrywomen matched her experience.

Despite her uniqueness—or perhaps because of it—Abigail Adams developed a keen sensibility to the liabilities of being born female in a paternalistic society. Her personal effort to overcome or adjust to these handicaps provided a conspicuous illustration of the plight of all American women. She denounced the potential for tyranny in the legal subjugation of wives to husbands, and she believed a woman should be free to make a prudent choice of a mate and to limit the number of children she bore. Refusing to accept the inferiority of the female intellect, she added her influence to the growing demand for the education of girls. Her acceptance of the doctrine of separate spheres for men and women fixed the boundaries of her feminism. But within these limits she maintained that the private political role of women in a republic was fully as important as the public one of the male.”

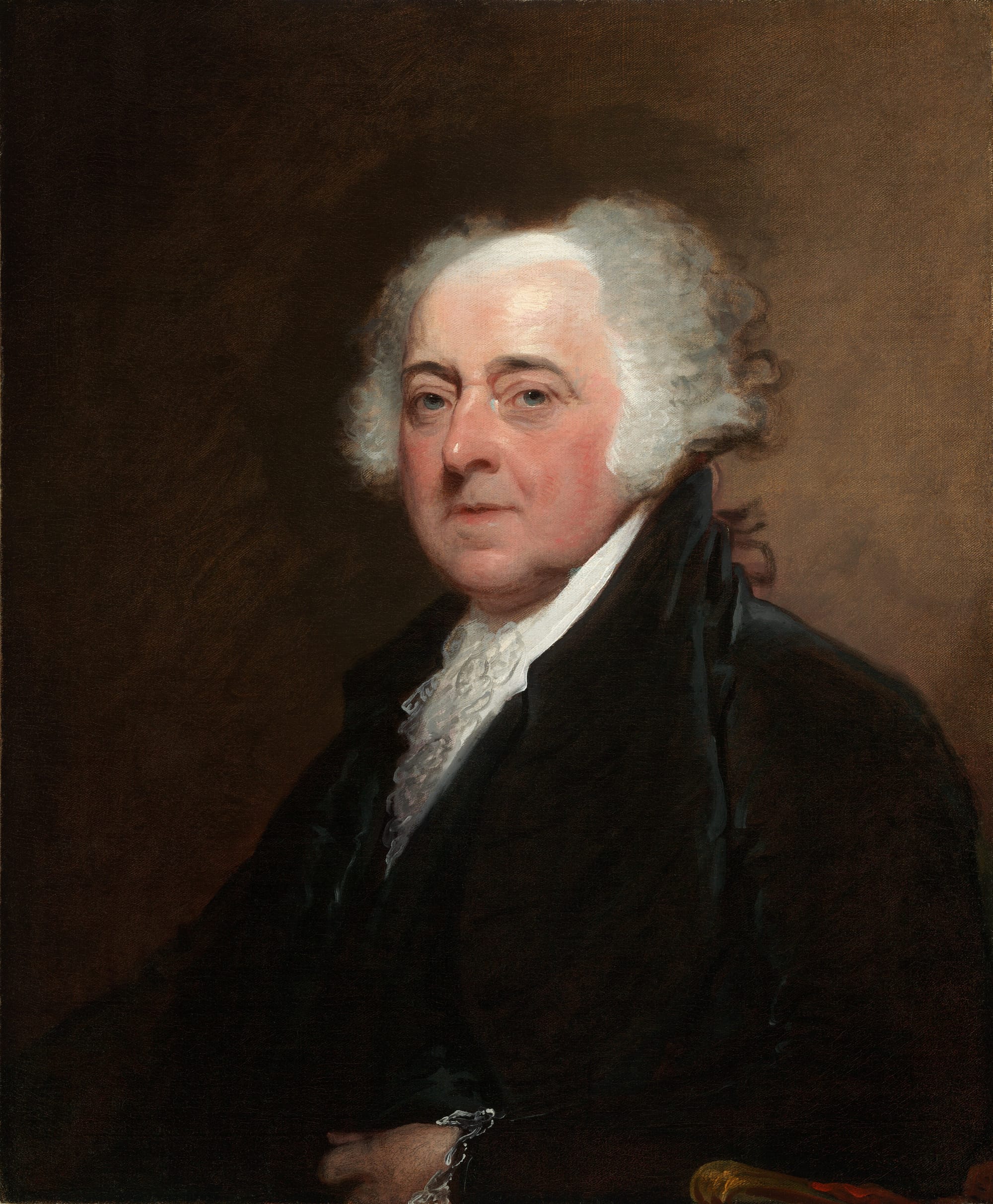

Despite the length of some of this season’s episodes, there was still a lot I was forced to leave out. Some things are better described in a book than in a podcast. If you’re interested in learning more about Abigail Adams, I’ve included a list of all the books I read on the website. You can find a link in the show notes for this episode. I’ve also included the final portraits painted of Abigail and John Adams on the web page for this episode.

I know we covered a lot of the same historical events in seasons one and two, but I hope you found it interesting to learn about the same events from different perspectives. I’m afraid we’re not able to leave behind the Revolutionary War just yet, because season three will cover Thomas Jefferson and his first ladies.

I say “ladies” plural because season three will be tricky. Jefferson’s wife Martha is considered an official First Lady, even though she died before he became president. His daughter, also named Martha, served as his de facto First Lady. So season three is going to cover both of them!

But first, we’ll take a couple of weeks off to let everyone recover from the end-of-year holidays. I’ll be back on January 16, ready to rock in 2026!

Thank you so much to everyone who has listened to the podcast, left a rating or review, or recommended the podcast to someone else. And to those who have reached out personally to tell me how much you’re enjoying the podcast, it really means the world to me. This podcast is a lot of work, but I’m loving it, and I have no intention of giving it up.

As always, every episode is produced by me, the music is by Matthew Dull, and I’m deeply grateful for all of you. See you next year, Happy New Year!