[Transcript]

Hello, and welcome to America’s First Ladies. I’m your host, Risa Weaver-Enion.

Episode 2.9 Life in London

We left off last week with John Quincy heading home to attend Harvard and Abigail, Nabby, and John leaving Paris for London where John would be the first minister from the United States of America to the Court of King George III.

This was a big deal, and even earned John a back-handed compliment from good old Minister Vergennes when John took his leave of the Court of King Louis XVI. Vergennes said it was a step down to go from the Court of France to any other court, even if a “great thing to be the first ambassador from your country to the country you sprang from.”

Abigail, for her part, was apprehensive about her role as the wife of the ambassador. She was worried about encountering hostility, having to socialize more, and of course, about the expense of it all. But she also had some confidence that she didn’t have when she had first arrived in London the previous July. Now she had been living abroad for 10 months and was more accustomed to things. She wrote, “I have seen many of the beauties and some of the deformities of this Old World. I have been more than ever convinced that there is no summit of virtue and no depth of vice which human nature is not capable of rising to.”

They arrived in London at the tail end of the high social season, when lots of people were in London instead of at their country estates. There was no official U.S. embassy or ambassadorial residence in London yet, and they had some trouble finding hotel rooms. They finally settled into the Bath Hotel, Westminster in Piccadilly. Abigail thought the area was “too public and too noisy for pleasure [but was] glad to get into lodging at the moderate price of a guinea per day for two rooms and two chambers.”

Unlike in Paris, Abigail was already immediately comfortable because she spoke the language. The simple necessity of giving directions to various servants was a million times easier in one’s native tongue.

While Abigail began the search for a more permanent residence for them, John set about his official duties. He reached out to the foreign minister, Lord Carmarthen, and they set an appointment. At that meeting, Carmarthen decided that John would be presented to King George the following Wednesday, after the levée. At the presentation would be only three people: John, Lord Carmarthen, and the King. In order to ensure that John didn’t commit any faux pas, the king’s master of ceremonies visited John to review the proper protocols.

On the appointed day, John dressed in a formal suit with a dress sword. At the presentation, John made three bows to the king: one upon entering, another in the middle of the room, and the final one just before the King. John later described the meeting to Secretary of State John Jay:

“I then addressed myself to his Majesty in the following words:—’Sir,—The United States of America have appointed me their minister plenipotentiary to your Majesty; and have directed me to deliver to your Majesty this letter which contains the evidence of it. … I think myself more fortunate than all my fellow-Citizens, in having the distinguished Honour to be the first to Stand in your Majesty’s Royal Presence, in a diplomatic Character; and I shall esteem myself the happiest of Men, if I can be instrumental in recommending my Country more and more to your Majesty’s Royal Benevolence, and of restoring an entire esteem, confidence and affection, or, in better Words, ‘the old good Nature and the old good Humour’ between People who, though separated by an ocean, and under different Governments, have the same Language, a similar Religion and kindred Blood.’

The King listened to every word I said with dignity…but with an apparent Emotion. Whether it was the Nature of the Interview, or whether it was my visible Agitation, for I felt more than I did or could express, that touched him, I cannot say. But he was much affected, and answered me with more tremor, than I had spoken with.”

For his part, King George was gracious, replying, “Sir,—The Circumstances of this Audience are so extraordinary, the language you have now held is so extremely proper, and the Feelings you have discovered, so justly adapted to the occasion that I must say that I not only receive with Pleasure, the Assurances of the friendly Dispositions of the United States, but that I am very glad the Choice has fallen upon you to be their Minister.”

But John knew that all George’s pleasant words were merely what was required of polite diplomacy. He finished his letter to John Jay, “We can infer nothing from all this concerning the success of my mission. Patience is the only remedy.”

Indeed, the London newspapers were much less gracious. The Public Advertiser wrote, “An ambassador from America! Good heavens what a sound!” The London Gazette referred to John as a “character.” The Daily Universal described it as a “notably cool reception.” And the Morning and Daily Advertiser said that John had been so embarrassed he was tongue-tied. John had his work cut out for him.

Three weeks later, Abigail and Nabby had to be presented to Their Majesties, the King and Queen. This was to take place at the Queen’s drawing room reception. Some of this is going to sound familiar from season 1 when I described the Drawing Room receptions that Martha Washington was required to host. This was the model for those, but on a much grander scale.

Abigail was not happy to find out that she would be required to attend these gatherings nearly weekly, worried about the expense, as usual. She wrote to Mary, “what renders it exceeding expensive is, that you cannot go twice the same season in the same dress.” She asked her dressmaker to make her something “elegant, but plain as I could possibly appear, with decency.”

Her dress for this first appearance was made of a glossy silk fabric, “covered and full trimmed with white Crape festoond with lilac ribbon and mock point lace, over a hoop of enormous extent; there is only a narrow train of about 3 yards length to the gown waist…ruffle cuffs for married Ladies, thrible lace ruffels, a very dress cap with long lace lappets, two white plumes, and a blond lace handkerchief.”

John also purchased for her two pearl hair pins with a matching necklace and earrings. Nabby was also dressed in white, with a petticoat and a cap with three immense feathers. They rode to the palace in their family carriage, which of course the catty London newspaper had words about. “Hearing the Honorable Mrs. Adams’s Carriage call’d was little better than going in an old chaise to market with a little fresh butter.”

The room they entered was filled with 200 guests, all standing. Abigail gave a very detailed account to Mary:

“The King enters the room and goes round to the right, the Queen and princesses to the left. Only think of the task the royal family have, to go round to every person and find small talk enough to speak to all of them. Though they very prudently whisper, so that only the person who stands next can hear what is said. … The Lord in Waiting presents you to the King and the Lady in Waiting does the same to Her Majesty.

The King is a personable man, but my dear sister, he has a certain countenance which you and I have often remarked, a red face and white eyebrows. … When he came to me…I drew off my right glove and His Majesty saluted my left cheek, then asked me if I had taken a walk today. I could have told His Majestry that I had been all morning preparing to wait upon him, but I replied, ‘No, Sire.’ ‘Why don’t you love walking?’ says he. I answered that I was rather indolent in that respect. He then bowed and passed on.

It was more than two hours after this before it came my turn to be presented to the Queen. The circle was so large that the company were four hours standing. The Queen was evidently embarrassed when I was presented to her. I had disagreeable feelings, too. She, however, said, ‘Mrs. Adams, have you got your house? Pray how do you like the situation of it?’ Whilst the Princess Royal looked compassionate, and asked me if I was much fatigued, and observed that it was a very full drawing room.”

Abigail then added a little cattiness of her own, telling Mary that the princesses were “well shaped, heads full of diamonds” but that Queen Charlotte was “not well shaped or handsome.” Altogether, she found the ladies of Court “very plain, ill-shaped, and ugly, but don’t tell anybody that I say so.”

Also, how amazing would it have been if Abigail had actually told King George that she hadn’t had time to go for a walk because she spent all day getting ready to meet him for ten seconds. It’s safe to say that John’s ambassadorship would have come to a hasty end.

Abigail finally found them a house near Hyde Park, which she compared to Boston Common, admitting that it was much larger and more beautiful than their hometown park. The house was in a fashionable neighborhood on Grosvenor Square, and she took some delight in noting that Lord North, the former Prime Minister who had pursued the war against the Americans, was now a neighbor living just opposite to them. Lord Carmarthen also lived just down the street.

With their furniture arrived from France, they moved in on July 2, the ninth anniversary of the vote for independence. The door opened into a large hall, and the first floor contained both a large dining room suitable for entertaining and another large room that John could use as an office for public business. The next floor contained a drawing room and library, and the bedrooms were on the third floor. The kitchen was in the basement, and the stables were out back. Abigail had a small room to herself where she could write and sew, and she had a view down to Grosvenor Square.

They once again had eight servants, which Abigail once again thought was too many. Esther Field was promoted to lady’s maid, John Briesler was one of two footmen, and there was also a butler, a housemaid, a cook, a kitchen maid, and a coachman. If you’ve ever watched Downton Abbey, you know what all those different servants do!

The city of London had a population of nearly a million people in 1785. It was not only the political capital of England, but also the center of manufacturing, finance, and trade. Via the Thames, ships could reach the English Channel and then the Atlantic Ocean. The Thames carried more traffic than any other river in Europe.

The Adamses went to the theater frequently, and of course went to church. Abigail was relieved to be out of Catholic France and back in a Protestant country. John’s primary job as ambassador was to negotiate a treaty of commerce with Britain. It’s what he had been trying to do as part of the commission in France, and now it was solely up to him. He also needed to ensure that both America and Britain abided by the terms of the peace treaty, which was not a given.

He wasn’t making much progress, being alternately snubbed and ignored. In one of his letters to Secretary of State John Jay he wrote, “Although I have been received here, and continue to be treated, with all the distinction which is due to the rank and title you have given me, there is, nevertheless, a reserve, which convinces me that we shall have no treaty of commerce until this nation is made to feel the necessity of it.”

As Edith Gelles explains in her book Abigail & John: Portrait of a Marriage, “Britain perceived no reason to fulfill any treaty obligations, because those in power didn’t expect the United States to continue as a nation. And for good cause. The states could not unite on the critical issues required for survival. There was no uniform currency. There were riots in some cities, such as Boston, indicating the inability of the government to suppress internal problems.

Further, as Lord Carmarthen pointed out to Adams, some Americans failed to pay their debts to English creditors. Individual states, such as Massachusetts, furthermore, had established trade barriers against British commerce. Finally, John learned that some states no longer bothered to send delegates to Congress, which hampered that body’s ability to act. From the British point of view, it was sheer hubris—if not comedy—for the American minister to send demands to the British government.”

By the end of that first summer, John had made no progress with Britain, but he was making progress with other nations. He was in talks with Prussia, Portugal, Denmark, and the Barbary States. Thomas Jefferson was also struggling with France, which was mired in a debt crisis that would eventually spark a revolution.

Meanwhile, Abigail and Nabby were dealing with their own difficult relationship, namely Nabby’s relationship with Royall Tyler. It had been more than a year since Nabby and Abigail left Massachusetts, and Tyler had been a very neglectful correspondent. Not only was he not writing to Nabby, but he wasn’t passing along the letters she included for friends when she sent letters to him. And her friends were also giving him letters, assuming he was writing Nabby regularly, which he also did not pass on.

By late summer, Nabby was convinced that he was not a suitable husband for her. As soon as she confirmed that her parents, primarily John, agreed, she sent Tyler a letter returning his letters and a miniature of him he had given her before she left. At this time period, this was a clear sign that their relationship and engagement were over.

It seems that Nabby dodged a bullet, because not long after this, Tyler fathered a child with his landlady, who was not only married, but already had six children. And then to top things off, Tyler eventually married an older half-sister of his own illegitimate child, and the child eventually went to live with her father and half-sister. So her half-sister was also her step-mother. I couldn’t make this stuff up if I tried. Tyler definitely was not a suitable husband for John and Abigail Adams’s only daughter.

Someone who was much more suitable was Colonel William Stephens Smith, who had served as one of General Washington’s aides-de camp during the war and had been named by Congress as the secretary to the American legation. Which means he was John’s secretary, because John *was* the American legation. Smith came from a respectable Long Island family and had attended Princeton.

One of Smith’s duties was to escort Abigail and Nabby to social events, so he got to know both of them quite well. He was apparently smitten with Nabby while she was still technically pledged to Royall Tyler, but Smith convenienty went to Prussia for four months at the tail end of 1785. By the time he came back, the Tyler situation had been settled, and he was free to court Nabby.

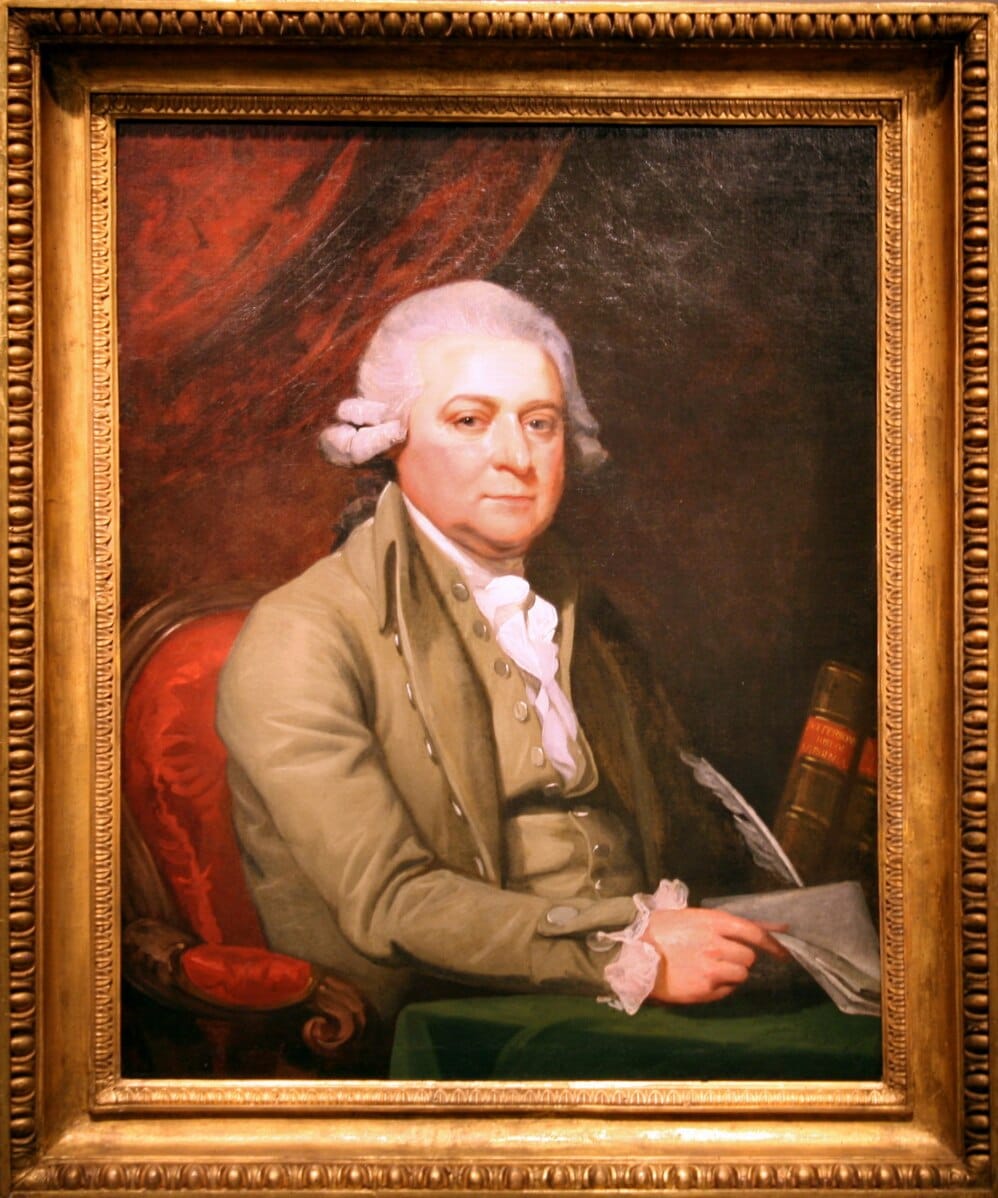

The Adamses were friends with a number of painters residing in London, most of whom were actually Americans. All three of them had portraits painted by Mather Brown. I’ll put the portraits on the website so you can view them and compare them to the early portraits of Abigail and John painted by Benjamin Blythe 20 years earlier.

London was even more expensive than Paris had been, and Congress had reduced John’s salary, so they continually worried about their expenses exceeding their income. Although, as we reviewed in detail in episode 2.8, Abigail was probably exaggerating the likelihood of that happening. A visiting Virginian commented that the dinner served by the Adamses was “plain, neat, and good.” And we all know how the Virginians liked to eat, so if it satisfied him, it must have been good enough to satisfy anyone.

For one dinner party given for several government ministers, Abigail was fortunate that an American sea captain had just made her a gift of a 114-pound sea turtle, which she served at dinner. She also had special tables built and purchased new linens, so money couldn’t have been that tight.

Abigail continued to enjoy going to the theater, but I can’t leave out her reaction to seeing Othello on stage, because it shows that even Abigail Adams, who abhorred slavery and would never in a million years have owned a person, had her racial prejudices. The role of Desdemona was played by a famous stage actress named Mrs. Sarah Siddons. She acted opposite her brother in many plays so she could play romantic parts without the scandal of being romantic with someone who wasn’t her husband. Side note: I’m not sure how it was better that she was acting out romantic scenarios with her brother, but apparently it was.

Anyway, if you’re at all familiar with the play Othello, you know that the character Othello is a Moor, which is how Europeans described North African and Iberian Muslims during the medieval period. In the play, Othello is a Venetian Moor, and is a Christian but also an African, which means he’s Black. Now, in 1785, there were no black actors. Sarah Siddons and her brother John Kemble were both white. You can probably see where I’m going with this. Yes, Kemble was in black-face for the performances.

In describing the play later to her sister Elizabeth, Abigail wrote, “I lost much of the pleasure of the play, from the Sooty appearence of the Moor. I could not Seperate the affrican coulour from the man, nor prevent that disgust and horrour which filld my mind every time I saw him touch the Gentle Desdemona.” Oh, Abigail.

To her credit though, she at least recognized that this was an unreasonable prejudice. In a letter to Colonel Smith, she wrote, “The liberal mind regards not…what coulour or complexion the Man is of.” She wasn’t sure why she had this prejudice against a Black man romancing a white woman, writing that she couldn’t tell, “Whether it arises from the prejudices of Education or from a real natural antipathy.” Either way, it’s not a good look for Abigail.

In March 1786 Jefferson arrived in London to see if he and John together could have more luck with the British. Jefferson had kept up an active correspondence with both John and Abigail. The letters with John were mostly business, but he and Abigail had become friends. They would often write and ask for the other one to acquire something they couldn’t get in their respective cities, some article of clothing or a book, etc.

After hanging around London for a month with no real progress, John and Jefferson decided to set out on a little tour of English homes and gardens. It would be John and Abigail’s first time apart since they had been reunited a year and eights months prior. John and Jefferson were gone for only a few days in early April, but even after returning to London, they made no progress with their negotiations. After doing some shopping (Jefferson loved to shop and spend money) and having his portrait painted by Mather Brown, Jefferson returned to Paris.

On June 12, 1786, Nabby and Colonel Smith were married in the house on Grosvenor Square. They had to get special permission from the Archbishop of Canterbury to hold the ceremony at home instead of in a church. There was no way these proud Protestants would let their daughter get married in an Anglican Church. The Anglicans might as well have been Catholics as far as the Adamses were concerned. Only a few friends were present, and the couple soon moved to a house on Wimpole Street. The bride was one month shy of her 21st birthday, and the rest of Abigail’s children were growing up too.

John Quincy had passed the Harvard entrance exam in March, after some remedial Greek lessons, at age 18. Charles, who was only 15, was already attending Harvard, his preparations by Elizabeth’s husband John Shaw clearly having done some good. Thomas was 13 and presumably still under the care of John and Elizabeth Shaw. With Nabby now living in her own home, this was the first time that Abigail had lived without any of her children in the same house. She was growing a bit tired of life abroad, writiing to her sister Mary, “I seem as if I was living here to no purpose, I ought to be at home looking after my Boys.”

In the summer of 1786, John, Abigail, Nabby, and William Smith took a week-long excursion to Essex, even visiting Braintree, England. Upon their return, John was called to The Hague on important business, and it seemed like a good opportunity for Abigail to see the city and country where John had spent so much of his time in Europe.

They spent five weeks in the Netherlands. Besides The Hague, they visited Rotterdam, Delft, Leyden, Haarlem, Amsterdam, and Utrecht. Abigail was becoming quite the well-traveled woman, and she was impressed with what she saw. The people were “well-fed, well-clothed, contented,” The cities were clean and orderly. “It is very unusual to see a single square of glass broken, or a brick out of place.” The Dutch were very welcoming to them, which Abigail took as “striking proof, not only of their personal esteem, but of the ideas they entertain with respect to the Revolution which gave birth to their connection with us. … The spirit of liberty appears to be all alive with them.”

The spirit of liberty also seemed to be alive and well in the farmers of Massachusetts. In March 1786, the Massachusetts legislature had levied heavy taxes on its residents. The farmers were already in debt and couldn’t afford these new taxes. When the legislature refused their request to print paper currency, the farmers revolted in a violent uprising known as Shays’s Rebellion because one of the movement’s leaders was Daniel Shays. They armed themselves and prevented the courts from convening by surrounding the courthouses. Abigail was distraught by the news and sad at the thought of her “Countrymen who had so nobly fought and bled for freedom, tarnishing their glory, loosing the bonds of society, introducing anarchy confusion and despotism, forging domestick Chains for posterity.”

In a letter to Jefferson, she wrote, “Ignorant, wrestless, desperadoes, who without conscience or principals, have led a deluded multitude to follow their standard, under pretence of grievances which have no existance but in their immaginations.” Jefferson replied with one of his most famous quotes, “The spirit of resistance to government is so valuable on certain occasions, that I wish it always kept alive. It will often be exercised when wrong, but better so than not to be exercised at all. I like a little rebellion now and then.” To which Abigail replied that an unprincipled mob was the “worst of all Tyrannies.”

Shays’s Rebellion was one of the instigating factors that led to the call for a revision of the Articles of Confederation which governed the union of the 13 states as one country. As we know, the Articles gave very little power to the federal government and were highly ineffective. They were part of the reason why John was failing to accomplish anything in London. Congress couldn’t prevent the states from violating the terms of the peace treaty, and Britain wouldn’t enter into any treaty of commerce with the U.S. until they held up their end of the peace treaty. It was a no-win situation for John.

In response to Shays’s Rebellion, and also in the hope that it would influence the gathering that would be responsible for revising the Articles of Confederation, John wrote a three-volume treatise titled A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America. In it, he laid out his ideas, which were very similar to what he had written back in 1776 in his Thoughts on Government. As it happens, the government structure adopted by the Constitutional Convention in 1787 was very similar to John’s ideal government of three co-equal branches and a two-house legislature.

Neither John Adams nor Thomas Jefferson was able to participate in crafting the new U.S. Constitution because they were both abroad the entire year of 1787. But the year was eventful for the Adamses in London.

In January, John informed Congress that he would serve one more year as ambassador to Great Britain and then return home. His complete lack of accomplishing anything of note was too much to bear, and he wanted to return home.

In April 1787, Nabby gave birth to Abigail and John’s first grandchild, a son they named William Steuben Smith. Fun fact: his middle name was in honor of Baron von Steuben who whipped the Continental Army into shape during the war. As one of George Washington’s aides during the war, William must have known von Steuben well.

In June 1787, Jefferson asked Abigail if she would mind taking in his young daughter Mary, called Polly, until he could come to London to retrieve her. Jefferson’s wife had died before he crossed the Atlantic to take his post as ambassador to France. His elder daughter Patsy had traveled with him, but Polly had been left behind in the care of an aunt. Polly was 8 years old when Jefferson decided to have her join him in Paris. She obviously couldn’t cross the Atlantic by herself, so a nurse was supposed to accompany her. Not many ships went from Virginia to Paris, so she was booked on a ship for London.

When Polly arrived on June 26, Abigail was surprised to see that the girl was accompanied not by an adult nurse but by a teenager. It turned out to be one of Jefferson’s slaves, a girl named Sally Hemings. The handful of days that Polly and Sally stayed with the Adamses in London is the only known instance of a slave living under their roof.

Abigail became very attached to the little girl, who was also quite attached to Abigail. For a young girl to lose her mother, and then to have her father move to another country without her, and then for her to be taken away from the aunt who had been caring for her for two years, and then to have to cross the ocean, and then to be taken away from the nice lady in London was really too much to ask an 8-year-old to bear. To top it all off, Jefferson didn’t even come to London personally to get his daughter. Instead he sent a valet who didn’t even speak English. Abigail almost didn’t let her go, but she had to.

Copies of the new U.S. Constitution reached London in the fall of 1787. John was mostly delighted with it, but he thought the office of the president should have been stronger. Jefferson was less pleased with the Constitution and thought the office of the president was too strong. It was the beginning of a division that would put them on opposite sides of politics for many years to come.

Next week, the Adamses will conclude their time abroad, return home to Braintree, and settle into a short period of private life before John finds himself elected vice-president.

Thanks for listening to this episode. It was produced by me, and the music is by Matthew Dull. If you’re enjoying the podcast, please tell a friend about it. Thanks!