[Transcript]

Hello, and welcome to America’s First Ladies. I’m your host, Risa Weaver-Enion.

Episode 3.1 Little Patty Wayles

Welcome back for season 3 of America’s First Ladies! This season we have a double-feature with two women named Martha Jefferson. Martha Jefferson the elder was Thomas Jefferson’s wife, and is considered an official First Lady, even though she died 18 years before Thomas was elected President.

Martha Jefferson the younger was the first-born daughter of Thomas and Martha Jefferson, and she stood in as hostess at the President’s House for her father sporadically during his two terms as President. Despite this, she is NOT considered an official First Lady.

But it’s my podcast, and I can do what I want, so we’re covering them both.

The elder Martha Jefferson was nicknamed Patty, and her daughter was nicknamed Patsy (just like Martha Washington when she was young). For the sake of clarity, I’m going to refer to the mother as Patty throughout. Especially because there are several other Marthas in this season. Here’s the good news though: the two Martha Jeffersons are the last two First Ladies named Martha, so we can finally leave this name behind after this season.

The overlap of names this season is going to reach epic proportions. And it’s not just first names, it’s also last names. A lot of these people intermarried within the same families, used last names as middle names, and sometimes even married cousins who had the exact same last name. It’s maddening.

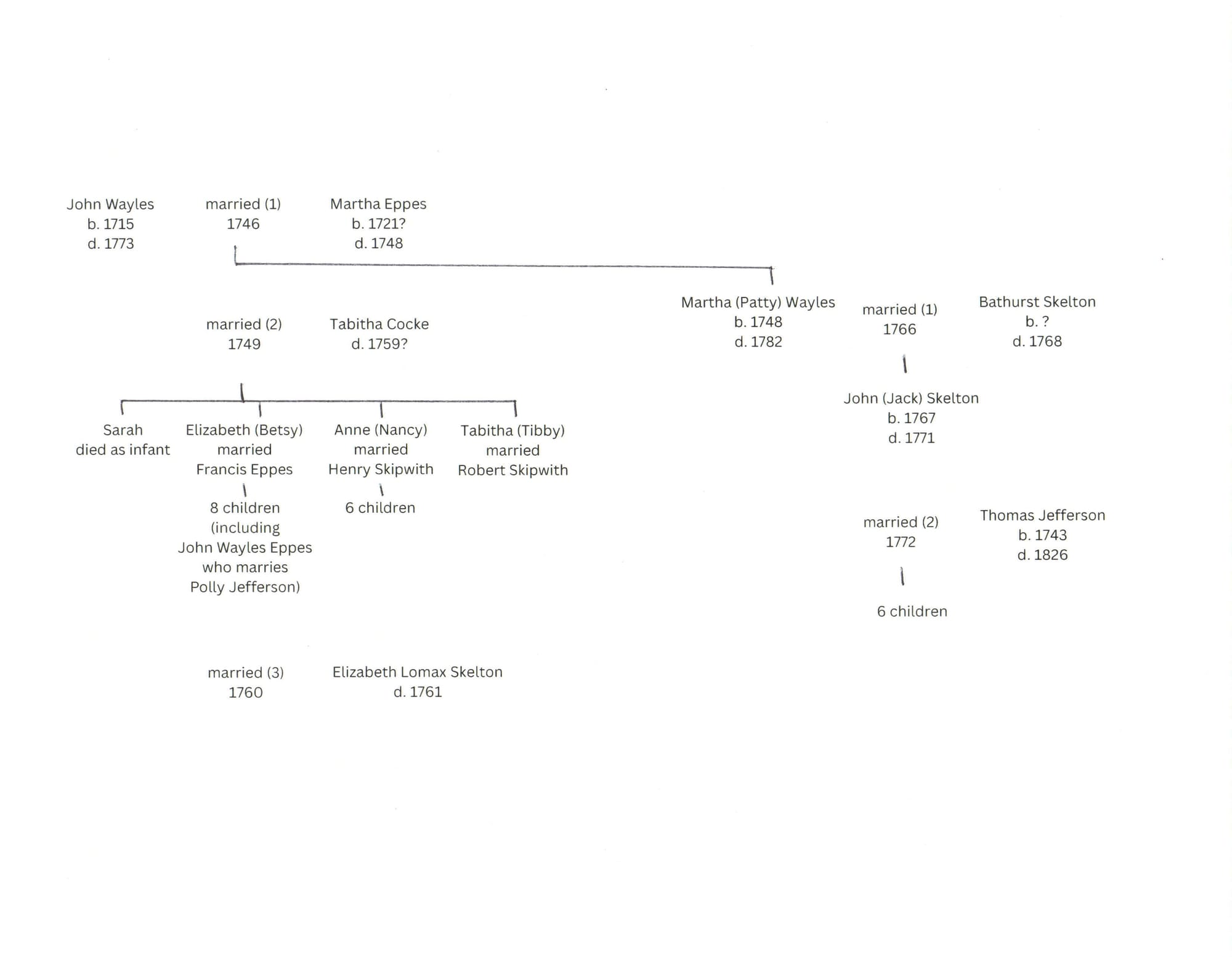

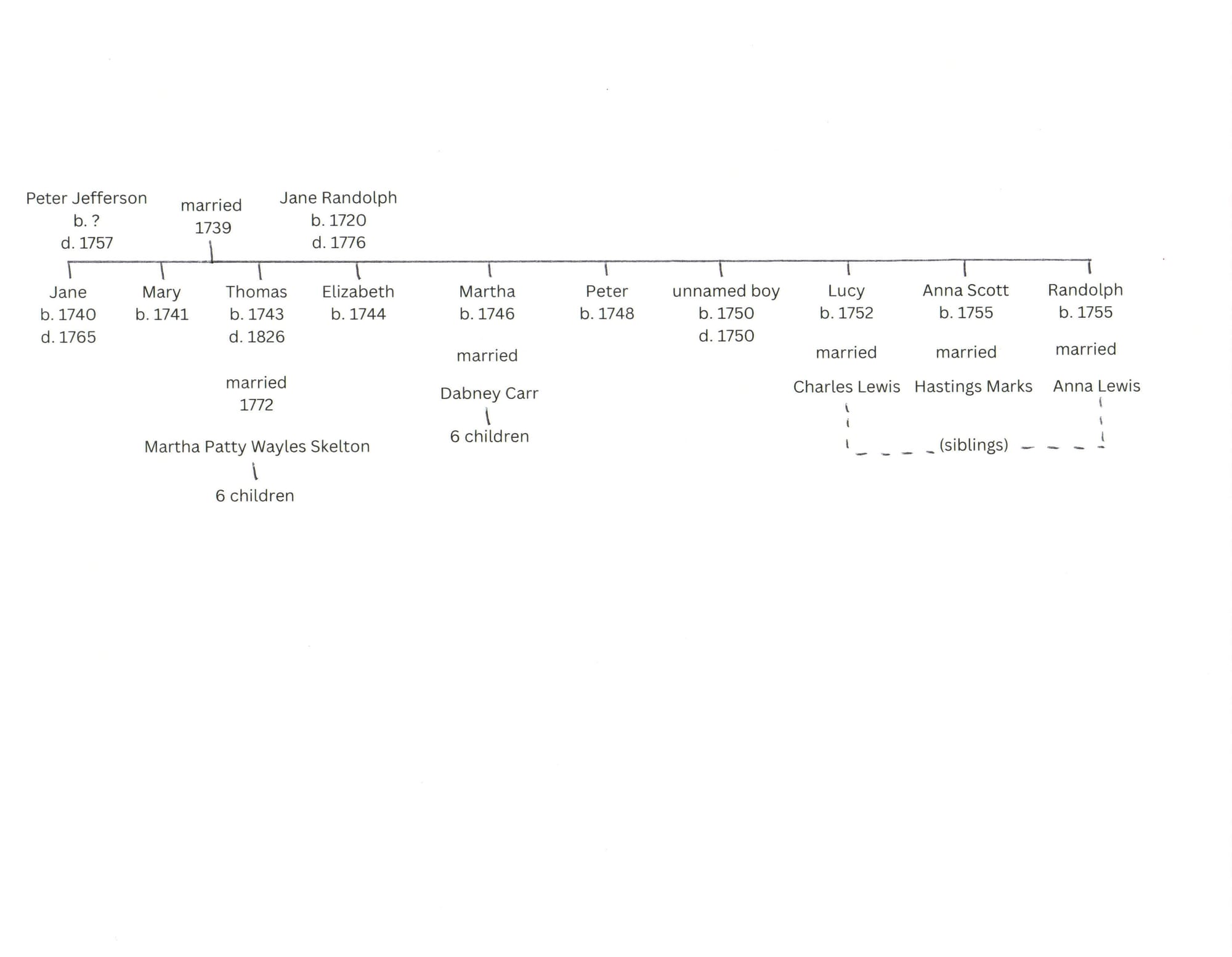

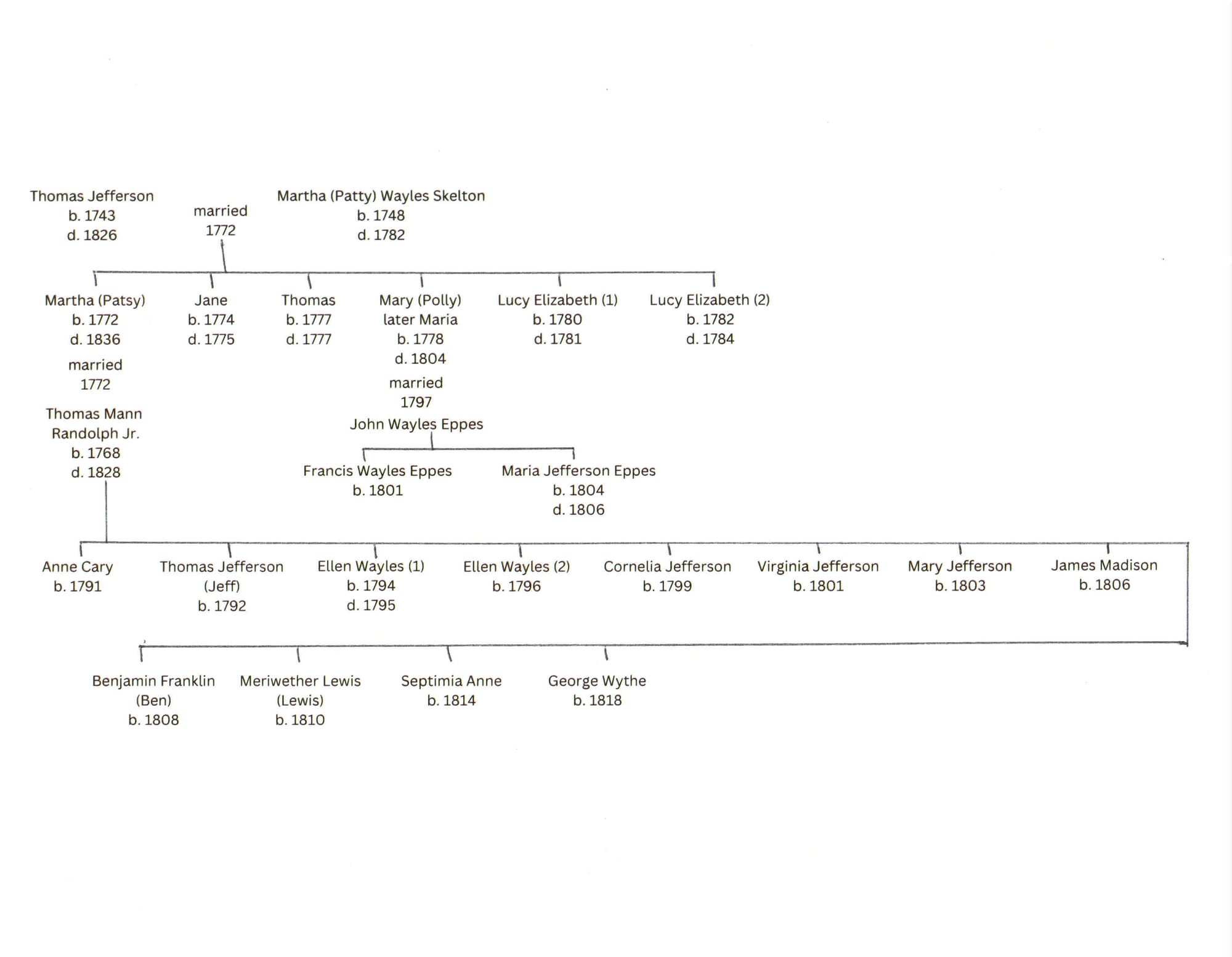

I created some genealogy charts for myself to use during the writing process, and I decided to put them on the website for this season, just in case you also want to see it laid out visually. It will also clarify the spellings for some of the names you’re going to hear over and over, so I really do encourage you to check those out.

I struggled to find thorough and accurate information about the elder Martha Jefferson. She’s not nearly as famous as our previous two subjects, Martha Washington and Abigail Adams, probably because she died young. It also doesn’t help that Thomas Jefferson burned all their letters after her death. Such a classic 18th century move.

But he went a step further and wrote to other people his wife had corresponded with, asked them to return her letters, and then burned those too. Bro was seriously concerned about protecting her privacy.

I only managed to read one book that focused on the elder Martha Jefferson, and honestly, the book was riddled with so many inconsistencies that I hesitate to put a lot of stock in it. It was published in 2015, so it’s not like it’s an old book or anything. I have no idea how the author, editor, and publishing house thought it was acceptable to publish a book that contradicts itself over and over again.

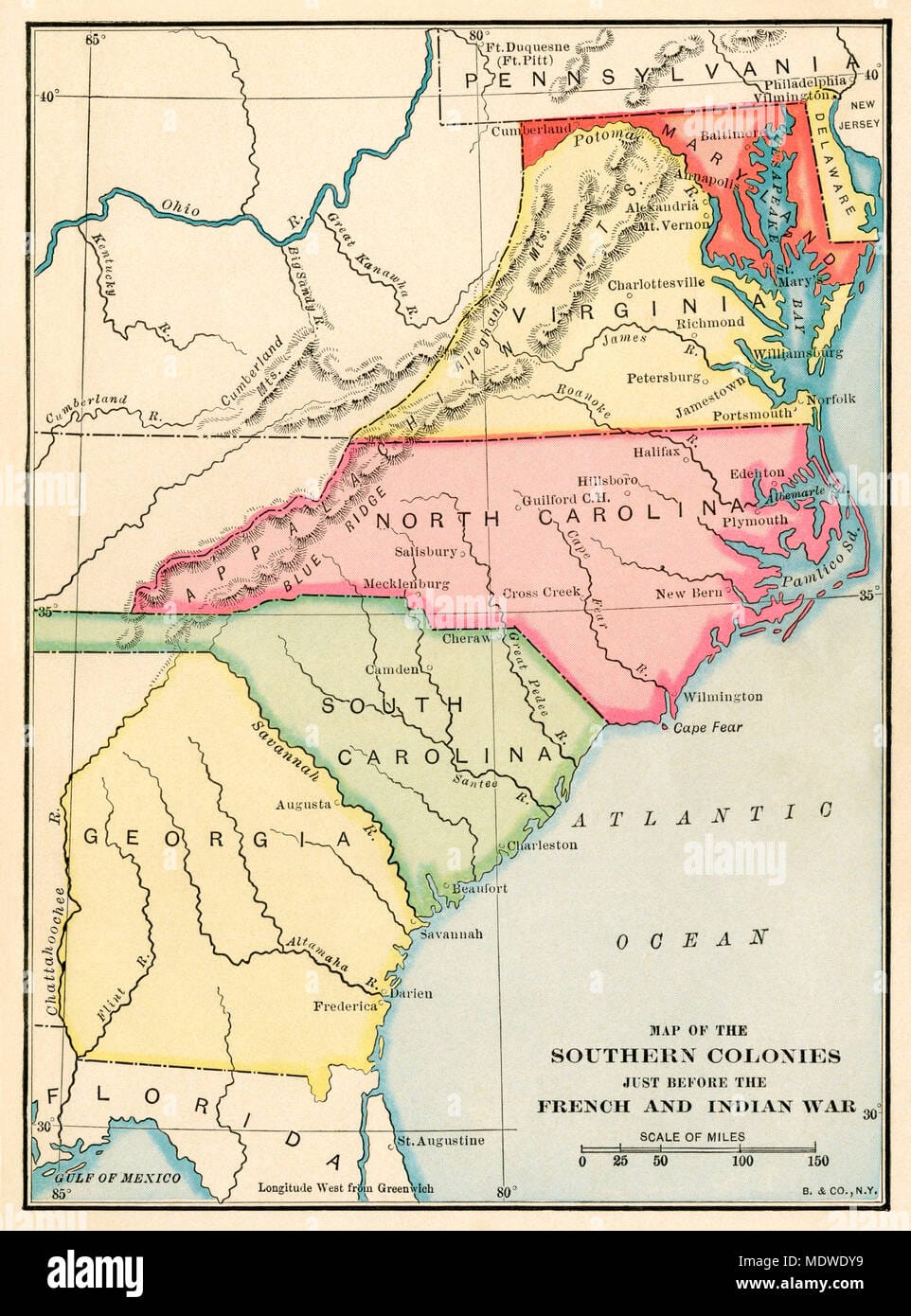

Even the source materials that historians rely on aren’t entirely accurate when it comes to Martha Jefferson. She was definitely born in Virginia, but there’s at least one source out in the world that says she was born in England. So I guess what I’m saying is, I’ve tried to present information that I’m reasonably confident is accurate. But I’ve generalized and made caveats where necessary because we just don’t have as much detailed information as I would like.

So with all that background information out of the way, let’s dive into Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson.

On October 19, 1748, a Virginia woman named Martha Eppes Wayles gave birth to a daughter. She and her husband, John Wayles, named the baby after its mother, calling her Martha Wayles, and nicknaming her Patty. When England switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar four years later in 1752, 11 days had to be added to the calendar. So the old October 19 became October 30. There’s no word on which date Patty celebrated her birthday.

Sadly, Martha Eppes Wayles never recovered from the ordeal of childbirth, and died shortly after giving birth to little Patty. This is almost all the information we have about Patty Wayles’s mother. She was likely born in April 1721, which would have made her 27 when she died.

We know that she married John Wayles in 1746, and we know that he was her second husband. Her first husband was a man named Lewellyn Eppes, Jr., who was a cousin of hers. So both her maiden name and her first married name were Eppes. But Lewellyn Eppes, Jr. died within a year of their marriage, and they had no children.

We also know that Martha Eppes Wayles’s father (Patty’s grandfather) was a man named Colonel Francis Eppes, but we don’t know much else about him. And we don’t even know who her mother was. The ancestors of Colonel Francis Eppes were some of the earliest arrivals to the colony of Virginia, arriving probably in the early 1600s. The Eppes family was one of the most prominent in Virginia, owning thousands of acres of land, and likely hundreds of slaves. So Patty’s mother was from a well-to-do family.

Patty’s mother had two siblings, an older brother named Francis Eppes and a sister named Anne Eppes. These names are going to turn up a lot in subsequent generations.

Patty’s father, John Wayles, had been born in England in 1715. He emigrated to the American colonies sometime in the 1730s. Sources are conflicted about whether he came to America as a servant to a prosperous family or had been trained in the law in England before emigrating.

Either way, he did work as a lawyer in Virginia. He was also a tobacco planter and a slave trader. Note that I didn’t just say “slave owner,” which, of course he was. I said “slave trader.” He made a lot of money buying and selling human beings. I hope you enjoyed the relatively slavery-free season 2, because we are back in Virginia this season, and our subjects’ relationship to slavery is even more difficult than the Washingtons’ was.

When John Wayles and Martha Eppes married in 1746, Martha brought considerable property to the marriage. Property that, of course, became entirely controlled by John Wayles as her husband. Martha had inherited the bulk of her first husband, Lewellyn’s, estate. And she also inherited from her father, Colonel Francis Eppes, some land, a house on Swan’s Creek, and three slaves. She shared these slaves with her sister Anne. And it wasn’t just these three enslaved people that Anne and Martha inherited; they also had the legal right to any offspring produced by their three slaves. Thus perpetuating the cycle of enslavement.

Martha’s older brother, Francis Eppes, had died in 1737, so she also inherited several things from him: “two Negro Girles named Kate and Bettey, also one hundred fifty pounds Current Money, and One Set of Silver Castors.” This inheritance was Martha’s for life, and then was to be further inherited by her heirs, forever. And the Betty named in that inheritance was one Betty Hemings, who would later bear a child you’ve probably heard of, Sally Hemings. More on both of them later.

So, Martha Eppes brought a fair bit of property to her marriage with John Wayles. And then she promptly died after giving birth to Patty, leaving Patty as her sole heir, with her fortune controlled by her father, John.

Thus, Patty Wayles grew up without her mother, without any grandparents on the Eppes side of her family, and presumably only with her Aunt Anne Eppes as the sole representative of her dead mother’s family.

Within a year of Martha Eppes Wayles’s death, John Wayles remarried, to a woman named Tabitha Cocke. Or it could be pronounced Cook. Or Coke. I have no idea. It’s spelled C-O-C-K-E, and this is the only time I’m going to have to say it out loud, so I’m not going to belabor the point.

John and Tabitha had four daughters together, who were technically Patty’s half-sisters, but I often refer to them throughout this season as her sisters, because that’s often how the sources refer to them. The four daughters were named Sarah, who died as an infant; Elizabeth, nicknamed Betsy; Tabitha, nicknamed Tibby; and Anne, nicknamed Nancy. You may recall that Martha Washington’s favorite sister Anna Maria was also nicknamed Nancy.

My curiosity finally got the better of me, and I researched why Nancy was a nickname for Anne or Anna. It turns out to have roots in medieval England. The short version is that the name Annis A-N-N-I-S was a form of the name Agnes. It was common to add the letter N to the front of a name to show affection. So adding N to Annis gets you to Nannis. Another form of Agnes was Ancy A-N-C-Y, so adding an N to Ancy gets you to Nancy. Eventually, Annis and Ancy seem to have turned into Anne and Anna, but the nickname Nancy stuck. Amazingly, this explanation also tells us how Nabby came to be a nickname for Abigail. It all comes together, folks!

Anyway, as far as I can tell, John and Tabitha were married for about a decade, from 1749 until around 1759, when Tabitha died. John married for a third time in January 1760, so Tabitha had to be dead before then, and Anne was born in 1756, so Tabitha died sometime between 1756 and 1759. John Wayles’s third wife was named Elizabeth Lomax Skelton. She was a widow with no existing children, and they had no children together, because she died about a year after they were married.

At that point, Patty would have been 12 or 13, and the other three girls would have been somewhere between 5 and 11 years old. John apparently decided that three wives was enough, and he never again remarried. He most likely relied on his household slaves to raise his four surviving daughters. He also may have had some female relatives who could help turn the young girls into proper ladies.

Patty was apparently not fond of either of her two stepmothers. The most concrete evidence for this comes from the fact that she made Thomas Jefferson promise never to remarry after her death, because she didn’t want her daughters subjected to a stepmother.

When Patty’s second stepmother died in 1761, Patty became the de facto woman of the house. Patty was probably taught most of the same things that our friend from season 1, Patsy Dandridge, was taught. After all, the two were both daughters of Virginia gentry, even though Patty Wayles was born 17 years after Patsy Dandridge.

Patty would have learned how to butcher hogs, cattle, and fowl; render lard to mix with lye and ashes for soap; brew beer; manage household goods and slaves; and oversee the kitchens and food supplies. Additionally, she learned to sew, do fine needlework, engage in polite conversation, play music, and dance. Patty Wayles was an accomplished musician, playing both the harpsichord and the pianoforte, as well as the guitar. She also had a lovely singing voice.

There’s no evidence that Patty’s portrait was ever painted, so we don’t really know what she looked like. We know from family descriptions that she was small, but we don’t know what her height might have been. Both Martha Washington and Abigail Adams were about 5 feet tall, and that seems to have been a fairly standard height for women in the 18th century. Some family members described Patty as “a little above medium height,” so maybe she was between 5’2” and 5’5”.

Patty probably had auburn hair and hazel eyes. She was described as fair-skinned, without freckles. She had a “lithe and exquisitely formed figure [and was] a model of graceful and queenlike carriage.” She also supposedly had a brilliant complexion and large, expressive eyes. I found an artist’s rendering of Patty that was painted in 1965. I’ve put it on the webpage for this episode. You can find the link in the show notes.

The plantation where Patty grew up was called The Forest. It was located in Charles City County, which was not far from the colonial capital of Williamsburg. It was located on the banks of the James River. Most plantations were situated close to rivers because it made shipping out the tobacco easier. The Forest was across the river from a plantation called Bermuda Hundred, which belonged to Colonel Francis Eppes, and is where Patty’s mother Martha grew up.

In the 1760s, the family seat of the Eppes family moved from Bermuda Hundred to a new plantation called Eppington. Patty Jefferson and her family spent a fair bit of time at Eppington over the years.

Because The Forest was reasonably close to Williamsburg, it’s presumed that Patty regularly attended social events in the capital city. She would have attended as her father’s escort after he was widowed a third time, and she also would have been the hostess of any events held at The Forest.

As William Hyland, Jr. writes in his book Martha Jefferson, “It is clear that, growing up, Martha knew how to manage a large household. Eventually running a bustling plantation with its vast estate, mansion, farms, large slave population, attendant overseers, and frequent guests and visitors (for both Wayles and, later, Jefferson) required considerable skill, work, and energy. Several sources note that, in addition to organizing the family affairs and ordering home supplies, Martha assisted her father in managing the plantation and home business accounts.”

Patty probably only learned enough math to balance the plantation account books, but we know she was well read, which is another interest she had in common with Thomas Jefferson. She seems to have been a fan of poetry and fiction. She also most likely learned French, which most young girls who were brought up to be “ladies” learned. And she was an accomplished rider; she and Thomas loved to ride horses together.

Patty probably had her fair share of suitors among the Virginia gentry, but we don’t have any information about any of them. We know that she married a man named Bathurst Skelton on November 20, 1766. Patty had just turned 18, and Bathurst was 22. If the name Skelton is tickling the back of your brain, it’s because John Wayles’s third wife was named Elizabeth Lomax Skelton.

Before marrying John Wayles, Elizabeth Lomax had married Reuben Skelton and then been widowed. Bathurst was Reuben’s younger brother. So in a very convoluted way, Patty married her step-uncle. But who knows if they looked at it that way.

The Wayles family and the Skelton family probably knew each other in general, because both families were from the same part of Virginia. And with Elizabeth Lomax Skelton being part of the Wayles family, even though only for a short time, it’s likely that Patty and Bathurst met at some sort of family gathering.

Bathurst had attended the College of William and Mary. Much like Harvard was THE college in Massachusetts, the College of William and Mary was THE college in Virginia.

After their marriage, Patty and Bathurst lived at Elk Hill, which was another plantation owned by John Wayles. It was within sight of Elk Island, where Bathurst owned his own 1000-acre plantation.

On November 7, 1767, just under a year after marrying Bathurst, Patty gave birth to a son, whom they named John, but called Jack. Then, not quite a year later, Bathurst died, on September 30, 1768. Patty was just about to turn 20, and was now a widow with a young son. The cause of Bathurst’s death is unknown, but he had made a will on his deathbed, and he left Patty his carriage and horses, along with a number of slaves, to be divided between little Jack and Patty if Jack survived to adulthood.

Patty and Jack left Elk Hill and returned to live at The Forest. She and her father John were the official guardians of Jack under the terms of Bathurst’s will. Patty resumed her former station as hostess of The Forest and social escort to her father.

There’s no definitive answer to the question of when Patty Wayles Skelton met Thomas Jefferson. We know that the first record of him visiting The Forest was in the fall of 1770. But he also attended the College of William and Mary, and he was only a year older than Bathurst Skelton, so it’s possible they knew each other from school and Patty met Thomas via Bathurst.

Thomas also took on Patty’s father John as a legal client in October 1768, so it’s possible that Patty and Thomas met then. Regardless, they did eventually meet and fall in love. So let’s get a little background on good old Thomas Jefferson.

Thomas was born on April 13, 1743, making him about five and a half years older than Patty. His birthday under the Julian calendar was April 2. Thomas was the third of ten children. I’ll quickly name them all, but you can see them in the genealogy chart on the website. Jane was the eldest, followed by Mary, Thomas, Elizabeth, Martha, Peter, an unnamed baby boy, Lucy, and twins named Anna Scott and Randolph.

As far as I can tell, only five of them lived long enough to marry and have children. His eldest sister Jane died at the age of 25, which deeply affected Thomas. She was one of only three people he ever composed an epitaph for. The other two were his wife and his best friend. Thomas’s sister Mary and his brothers Peter and the unnamed boy all seem to have died as infants or children. His sister Elizabeth died in 1774, when she was probably in her late 20s, but there’s no mention of any surviving children, so she may have been a spinster, which just means an unmarried woman.

His younger sister Martha went on to marry his best friend, Dabney Carr, and they had six children. His younger sister Lucy married a family cousin named Charles Lewis. Thomas’s younger brother Randolph also married a Lewis cousin, Charles’s sister Anna. So, brother-sister siblings married brother-sister siblings, who also all happened to be first cousins. The fun never ends with this family. Randolph’s twin sister Anna Scott married a man named Hastings Marks. Seriously, look at the genealogy if you’re confused. It’s a super confusing family tree.

Thomas Jefferson’s parents were Peter Jefferson and Jane Randolph. The Randolph family was another one of the most prominent families in Virginia, and Peter definitely married up when he married Jane.

Thomas was born at the family plantation called Shadwell, in Albemarle County, a few miles from Charlottesville. Peter Jefferson was a planter and surveyor, but not a highly educated man. He couldn’t read Latin or French, according to most sources.

Jane Randolph had been born in London and emigrated to Virginia with her parents in 1725, when she was about four years old. The parish in London where Jane was born was called Shadwell, which explains how that came to be the name of the plantation where Thomas grew up.

Peter Jefferson died in 1757, when Thomas was 14. His mother Jane remained a strong force and influence in his life. William Hyland, Jr. quotes author Jon Meacham, who wrote, “Jane almost certainly exerted as great an influence on her eldest son as the legend of Peter Jefferson did—but in subtler ways. Jane ran things as she deemed. Literate, social, fond of cultivated things—from fancy china to well-made furniture to fine clothing—she was to endure the death of a husband, cope with the deaths of children, and remain in control to the end, immersed in the plantation around her and in the lives of those she loved.”

The Jeffersons valued education, and Thomas was no different. He spent a great deal of his youth reading and learning, when he wasn’t outside engaged in physical activity. Thomas despised laziness, writing to one of his daughters years later, “Of all the cankers of human happiness, none corrodes it with so silent, yet so baneful, a tooth, as indolence. Knowledge, indeed, is a desirable, a lovely possession.”

In 1761 Thomas enrolled at the College of William & Mary, when he was 18. He studied mathematics and philosophy, among other subjects, and then he apprenticed as a law clerk with George Wythe. He was admitted to the bar in Virginia in 1766.

By the time Thomas started courting Patty Wayles Skelton in late 1770, he already had the location of his future home at Monticello picked out. It was at the top of a hill, not far from Shadwell. There was no home there yet, and Thomas would build and re-build on that site for the rest of his life. His family home at Shadwell had burned down earlier in 1770, destroying all of his books and papers. One of the family slaves managed to save his violin.

Thomas and Patty had many things in common, some of which I’ve already mentioned. They were both talented musicians, she on the harpsichord and pianoforte, he on the violin. They both loved reading and literature. They were both avid riders. As a young widow of 22 with a three-year-old son, Patty had a maturity that seems to have appealed to Thomas.

Thomas was tall and lanky. He stood about 6’2” or 6’3”, and had reddish hair that he wore long in a ponytail called a queue. He neither wore a wig nor powdered his hair. He had a fair, freckled complexion and hazel eyes. His portrait was painted for the first time in London by Mather Brown. It was during his visit to London with John and Abigail Adams, and John is the one who insisted that Thomas have his portrait painted. I’ll put it on the website along with the artist’s rendering of Patty.

I obviously quoted David McCullough’s book John Adams a lot in season 2, but McCullough wrote a surprising amount about Thomas Jefferson in that book, so I’ll quote him again this season. McCullough described Thomas as usually standing, “with his arms folded tightly across his chest. When taking his seat, it was as if he folded into a chair, all knees and elbows and abnormally large hands and feet.

Where Adams was nearly bald, Jefferson had a full head of thick coppery hair. His freckled face was lean like his body, the eyes hazel, the mouth a thin line, the chin sharp. Jefferson was a superb horseman, beautiful to see. He sang, he played the violin.

He was as accomplished in the classics as Adams, but also in mathematics, horticulture, architecture, and in his interest in and knowledge of science he far exceeded Adams. Jefferson dabbled in ‘improvements’ in agriculture and mechanical devices.

His was the more inventive mind. He adored designing and redesigning things of all kinds. Jefferson, who may never have actually put his own hand to a plow, as Adams had, would devise an improved plow based on mathematical principles, ‘a moldboard of least resistance.’”

It was likely a combination of Thomas’s intelligence, good looks, and musical talents that attracted Patty to him. Thomas also seemed to be fond of Patty’s young son Jack, which was undoubtedly important to her. Sadly, Jack died either on June 9 or 10, 1771, of unknown causes, but likely a fever, perhaps accompanied by an ear infection.

It seems likely that Thomas’s courtship of Patty had to be put on hold after the death of her child. To have a child survive the dangers of infancy only to die at the age of 3 ½ seems like an especially hard burden to bear. Presumably it was some comfort for Patty to have Thomas in her life. We can’t say for sure without their letters.

There’s some indication that Patty’s father John was reluctant for her to marry Thomas. In a letter written to a friend in February 1771, Thomas complained that “the unfeeling temper of a parent” could obstruct a marriage, but he may not have been talking about his own situation.

There was also the slight wrinkle that John Wayles was loyal to the English crown, and actually served as an agent for British merchants, collecting debts owed to the British by his fellow Virginians. He may not have liked the fact that his daughter’s suitor was outspoken against the crown and had supported the nonimportation agreements the Virginia Burgesses voted on in response to the hated Townshend Acts.

But despite all that, John Wayles eventually consented to the marrige in November 1771, and they set a wedding date of January 1, 1772. Thomas was quite a busy man during his courtship of Patty. He had a law practice in Charlottesville, which required him to travel around Viriginia to serve clients, much like John Adams had done in Massachusetts. In 1769 he had also become a member of the House of Burgesses, which met in Williamsburg. And he was working on building a home at Monticello. But he found the time to purchase a marriage license on December 30, 1771.

Patty and Thomas were married at The Forest, and it seems that the parlor was filled with family and friends. The bride was 23, and the groom was 29. We have no evidence for what either of them wore on their wedding day, nor do we have any details about the ceremony or celebrations. Knowing what we do about Virginia weddings from season 1, it’s safe to say that there was a lot of music, dancing, and drinking, and that the festivities lasted for a week or so. I like to picture George and Martha Washington celebrating their 13th wedding anniversary at Mount Vernon while Thomas and Martha Jefferson were celebrating their wedding 150 miles away at The Forest.

Sometime shortly before or just after their marriage, Thomas presented Patty with a gift: an elegant solid mahogany pianoforte that he had ordered from London, specifying that it should be “worthy the acceptance of a lady for whom I intend it.”

The new Mr. and Mrs. Jefferson stayed at The Forest until January 18, when they departed for Monticello. That winter was quite snowy—at one point in January, Virginia received more than 3 feet of snow in one blizzard, which was the greatest snowfall since the settlers had arrived more than 100 years before.

The journey from The Forest, which was near Williamsburg, to Monticello, which was near Charlottesville, was more than 100 miles, so the Jeffersons made several stops along the way to break up the long journey. Their first stop was a plantation called Shirley, owned by Charles Carter, one of Thomas’s friends from the College of William and Mary.

Then they stopped at a plantation called Tuckahoe, where Thomas had lived with his family for a few years during his youth. Next up was Elk Hill, which was Patty’s plantation, and the home where she had lived with her first husband, Bathurst.

Their final stop was Blenheim, where it was snowing so heavily that their coach could no longer travel the road, let alone the steep hill leading to Monticello, which translates to “Little Mountain.” So they borrowed saddles at Blenheim and rode the final eight miles on horseback, through snow drifts as high as two feet. Clearly, Patty and Thomas were eager to get to their new home and their new life together.

Next week, we’ll join the Jeffersons at Monticello and hear about their married life together, a period that Thomas later referred to as “ten years of unchequered happiness.”

Thanks for listening to this episode. It was produced by me, and the music is by Matthew Dull. And I’m going to keep reminding you to leave a rating or review for the podcast, because those really help new listeners find the show. But I will note that not all podcast players have this capability. As far as I know, you can only write a review via Apple Podcasts, and Spotify will let you give a five-star rating, but not write a review. Other players do not seem to allow for either, just to make my life harder.